Integrated Services

Jump to a Section

Before You Dive In

On Demand Webinar

Learn how to promote positive mental health throughout the day. This webinar provides foundational information that guides the implementation of all aspects of Every Moment Counts.

Downloadable Materials

Use the following materials for ideas on integrating services for a more inclusive classroom.

Check it Out! Inclusive Classroom Video Clips

Video #1: Embedded Strategies for Creating an Inclusive Classroom - Small OT activity group focusing on mental health literacy (2 minutes)

Video #2: Co-teaching self-regulation - The third grade students in this video are engaged in a co-taught lesson by an occupational therapist, intervention specialist and school counselor (2.5 min.)

Video #3: Co-teaching - An OT discusses co-teaching lessons on social and emotional learning (SEL) to foster an inclusive classroom environment (MCaLT)

Video #4: Integrating Related Services Into Community-Based Instruction - Therapists worked collaboratively with the intervention specialists to address a variety of IEP goals

MCaLT: Making Connections & Learning Together

MCaLT e-Manual: The full MCaLT manual is available for download (below).

Introduction: Integrated Services for an Inclusive Classroom

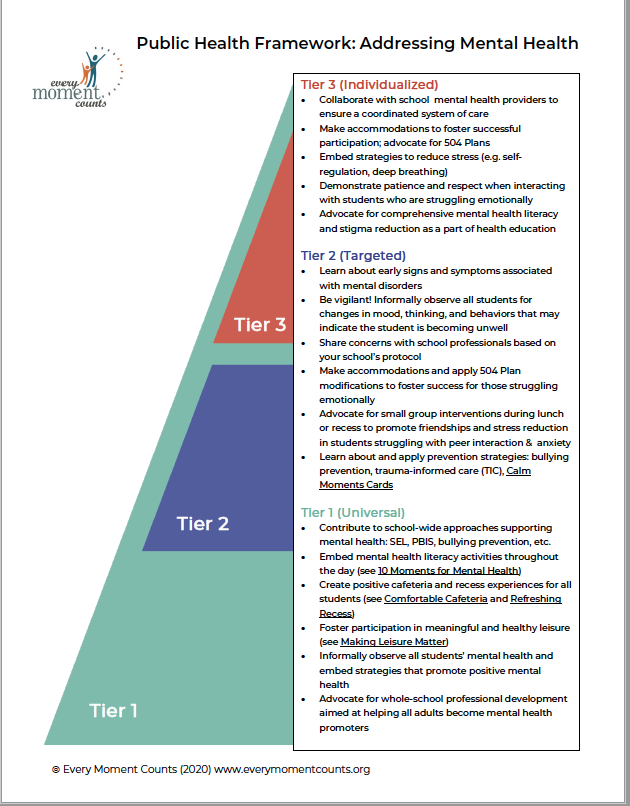

A major focus of the Integrated Services Initiative is creating an inclusive classroom environment by maximizing the impact of related services (e.g. occupational therapy, speech language pathology, school counseling, physical therapy, school nurses, etc.) by providing therapy in the general education natural context as much as possible.1 This is in contrast to pulling students out of class to provide services in isolated therapy rooms. Integrated services aimed at facilitating an inclusive classroom give practitioners access to all students, not just those on their caseload. Opportunities to provide universal (Tier 1) and targeted (Tier 2) services are enhanced when integrating services throughout the day.

This section of the website provides information about why integrated services represents ‘best practice’ in schools and how inclusive classrooms benefit all students with and without disabilities and/or mental health challenges. Examples of how to provide integrated services focusing on mental health at Tiers 1, 2, and 3 are shared.

This section of the website provides information about why integrated services represents ‘best practice’ in schools and how inclusive classrooms benefit all students with and without disabilities and/or mental health challenges. Examples of how to provide integrated services focusing on mental health at Tiers 1, 2, and 3 are shared.

1Cahill, S., & Bazyk, S. (2019). School-Based Occupational Therapy. In Jane Clifford O’Brien & Healther Kuhaneck (eds.). Case-Smith’s Occupational Therapy for Children & Adolescents (8th edition). Mosby.

Remember this:

Every Moment Counts aims to maximize the impact of related services by integrating therapy throughout the day in inclusive classrooms and a variety of other school contexts.

Integrated services, inclusive classrooms, and school mental health

Addressing children’s mental health is far too complex to relegate to a small number of licensed mental health providers (generally 1-2 per school). Leaders in school mental health (SMH) are calling for a paradigm shift to prepare all frontline workers to contribute to children’s mental health.1 In particular, it is important to utilize all indigenous resources - professionals who have a background in addressing mental health and can contribute to mental health promotion and prevention efforts. In addition to school counselors, psychologists, and social workers, the following health professionals have entry-level knowledge and skills in addressing mental health, including:

Addressing children’s mental health is far too complex to relegate to a small number of licensed mental health providers (generally 1-2 per school). Leaders in school mental health (SMH) are calling for a paradigm shift to prepare all frontline workers to contribute to children’s mental health.1 In particular, it is important to utilize all indigenous resources - professionals who have a background in addressing mental health and can contribute to mental health promotion and prevention efforts. In addition to school counselors, psychologists, and social workers, the following health professionals have entry-level knowledge and skills in addressing mental health, including:

- Occupational therapists (OT) and OT assistants (OTAs)

- School nurses

- Music therapists

- Recreation therapists

It is important to include these school providers as team members who can collaborate with licensed mental health providers and frontline school personnel in order to contribute to mental health promotion, prevention, and intervention.

1Atkins, M. S., Hoagwood, K. E., Kutach, K., & Seidman, E. (2010). Toward the integration of education and mental health in schools. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 37, 40-47.

Special education related services embedded in natural settings (classroom, art, cafeteria, recess, after-school) versus isolated therapy rooms address the needs of students with disabilities without removing them from class time. Emphasis in an inclusive classroom should be on using nonintrusive methods that seamlessly fit into the student’s school day. Such integrated services foster social interaction and friendships among students with and without disabilities. In addition to addressing the needs of students with disabilities, integrated services also promote positive mental health and academic success in students at-risk of developing mental or physical health challenges as well as those without disabilities.1

Keep in mind that “students with disabilities do not attend school to receive related services; they receive services so they can attend and participate in school.”2

Why are integrated services ‘best practice’?

1) It’s the law! IDEA (Individuals With Disabilities Education Act) does not specify the type of service delivery provided, but it does indicate that all related services be provided in the LRE (lease restrictive environment) to foster participation in the general education curriculum. Simply stated, integrating therapy services (OT, PT, SLP) in general education settings to the maximum extent possible with an inclusive classroom is the law.1

2) Learning new skills occurs best in the ‘real’ environment. Research on motor learning indicates that the practice of a new skill in the setting where it is naturally performed is most effective for developing new skills.3 Pull-out services in isolated therapy rooms filled with contrived activities and equipment are no longer considered best practice in schools. Such services may only be appropriate during initial stages of learning a task.

2) Learning new skills occurs best in the ‘real’ environment. Research on motor learning indicates that the practice of a new skill in the setting where it is naturally performed is most effective for developing new skills.3 Pull-out services in isolated therapy rooms filled with contrived activities and equipment are no longer considered best practice in schools. Such services may only be appropriate during initial stages of learning a task.

3) Students benefit. When services are integrated students with disabilities and mental health challenges get to participate fully in school. Pulling students out of the classroom for therapy is disruptive to their education and social participation. In addition, students with disabilities benefit from the teacher’s ability to carry over therapy strategies throughout the day. In a study of fine motor and emergent literacy outcomes with an inclusive classroom that fully integrated occupational therapy in a kindergarten curriculum, researchers found that children with and without disabilities made significant gains in fine motor and emergent literacy skills.4

4) Therapists gain a fuller picture of the student’s abilities and challenges. Providing services in the natural setting of an inclusive classroom helps therapists learn about the academic and behavioral expectations, teacher preferences, and unique culture of each classroom. Therapists are able to analyze the relationships among the child's abilities, activity expectations, and physical and social environment more fully. When the task-environment demands are greater than the student's abilities, the therapist and teacher must adapt the environment or task to foster successful participation. Integrated therapy ensures that the therapist's focus has high relevance to the performance expected in the student's classroom and other school contexts.1

5) Teachers and other school personnel benefit from observing therapists model interventions. With integrated services school personnel have a chance to learn about the specific role of the different therapies (OT, PT, SLP) and other related service providers (e.g. school counselors). For example, a teacher may learn how to modify the classroom environment in order to meet the sensory needs of students. Cafeteria and recess supervisors learn how therapists foster mealtime conversations, social interaction, and active play.

Integrated services requires close collaboration among all relevant school personnel (therapists, teachers, para-educators, counselors, etc.). Findings from studies have indicated that the greatest challenge associated with providing integrated services is time for school personnel to meet and plan embedded services.5 Although informal collaboration with teachers in the hallways or during lunch is useful, time for regular formal meetings is essential.

Planning time is essential to creating a more inclusive classroom - and more inclusive school experiences overall.

1Cahill, S., & Bazyk, S. (2019). School-Based Occupational Therapy. In Jane Clifford O’Brien & Health Kuhaneck (eds.). Case-Smith’s Occupational Therapy for Children & Adolescents (8th edition). Mosby. 2Giangreco, M. F. (2001). Guidelines for making decisions about IEP services. Montpelier, VT: Vermont Depart¬ment of Education. 3O’Brien, J., & Lewin, J. E. (2008). Part 1: Translating motor control and motor learning theory into occupational therapy practice for children and youth. OT Practice, 13(21), CE 1–8. 4Bazyk, S., Goodman, G., Michaud, P., Papp, P., & Hawkins, E. (2009). Integration of occupational therapy services in a kindergarten curriculum: A look at the outcomes. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63, 160-171. 5Bose, P., & Hinojosa, J. (2008). Reported experiences from occupational therapists interacting with teachers in inclusive early childhood classrooms. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 62, 289–297. doi:10.5014/ajot.62.3.289

Remember this:

HOW to Integrate Services

- Modify the environment and/or task

- Co-teaching strategies

- Coaching strategies

- Small group interventions

- Whole-school, universal programs

HOW to provide integrated services?

Related services can be integrated throughout the day using a combination of informal and formal strategies. Informal strategies include modifying the environment (physical, social, sensory) and/or the task to foster successful participation and mental health. Formal strategies include co-teaching in inclusive classrooms, coaching, small group interventions, and universal programs. Learn more about this strategies below.

Related services (OT, SLP, counseling) can be embedded throughout the school day to enhance participation and mental health in a number of ways, including the following:

Reframe the teacher’s perspective. Examples: Explain how anxiety or depression may impact concentration and give suggestions for simplifying instructions; describe how sensory processing challenges might impact function, social participation, and mood. Problem solve how to make accommodations and create a more inclusive classroom to foster successful participation (e.g. having a quiet corner for a calming break; giving feedback using a soft voice, etc.).

Reframe the teacher’s perspective. Examples: Explain how anxiety or depression may impact concentration and give suggestions for simplifying instructions; describe how sensory processing challenges might impact function, social participation, and mood. Problem solve how to make accommodations and create a more inclusive classroom to foster successful participation (e.g. having a quiet corner for a calming break; giving feedback using a soft voice, etc.).

Modify the activity or task. Examples: Recommend the use of sound deafening earphones for a student with auditory hypersensitivity when participating in loud settings; break large assignments down into smaller steps for a student with anxiety; use a visual schedule to help a student anticipate transitions throughout the day.

Modify the physical environment. Examples: Provide a quiet and calming area of the classroom for students who feel overwhelmed or agitated; provide sensory materials for self-regulation such as fidget toys, weighted lap pads, or wiggle cushions.

Modifying the social environment. Examples: Implement a ‘buddies’ program to foster interaction and friendships between students with and without disabilities; have students read books on topics related to friendship, empathy, and respect for differences followed by discussions on how to demonstrate these qualities throughout the day.

Improve the student’s skills. Examples: Teach all students strategies that promote feelings of emotional well-being such as deep breathing, taking movement breaks, and how to self-regulate.

To help teachers and other frontline personnel to implement any of the above strategies for a more inclusive classroom, the therapist uses modeling and coaching as the student attempts the activities in his or her natural routine.1

1Cahill, S., & Bazyk, S. (2019). School-Based Occupational Therapy. In Jane Clifford O’Brien & Health Kuhaneck (eds.). Case-Smith’s Occupational Therapy for Children & Adolescents (8th edition). Mosby.

What is co-teaching?

Although co-teaching originally was designed as an instructional strategy for general and special educators to share teaching within an inclusive classroom,1 it has also been used by related service providers (counselors, OTs, SLPs, RNs, etc.) as a formal way to integrate services.2 Cook and Friend define co-teaching as “two or more professionals delivering substantive instruction to a diverse, or blended, group of students in a single physical space” (p.1).1 In general, co-teaching involves collaboration to design, plan, implement, and evaluate the learning experience.

Five variations of co-teaching have been described:

- one teaching and one assisting (e.g. occupational therapist takes the lead and teacher assists, or vice versa);

- station teaching (teachers divide instructional content into two or more segments; part of the content is taught to part the class at the same time by different teachers/therapists; instruction is rotated with all groups);

- parallel teaching (one unit of instruction is taught simultaneously to separate class groupings, resulting in a lower student-to-teacher ratio);

- alternative teaching (one person teaches a small group of students who need specific accommodations while the other teaches the remaining larger group);

- team teaching (both teachers teach at the same time, sharing the lead in the discussion).1

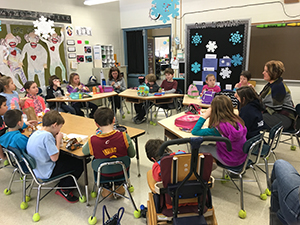

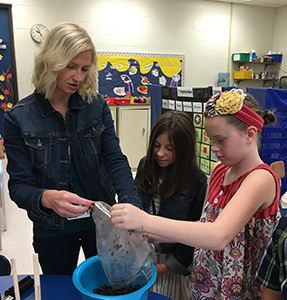

Related service providers might co-teach content without the teacher involved in planning depending on the curricular needs. For example, an OT might co-teach lessons on self-regulation and coping strategies as depicted in the photo. Carol Conway, MS, OTR/L routinely co-teaches lessons on the Zones of Regulation3 and mental health literacy with the school counselor at Hudson City Schools in Ohio. This has become a part of the general education curriculum.

Related service providers might co-teach content without the teacher involved in planning depending on the curricular needs. For example, an OT might co-teach lessons on self-regulation and coping strategies as depicted in the photo. Carol Conway, MS, OTR/L routinely co-teaches lessons on the Zones of Regulation3 and mental health literacy with the school counselor at Hudson City Schools in Ohio. This has become a part of the general education curriculum.

Counting IEP minutes? The provider's time is scheduled for the co-teaching activities, rather than for individual sessions. Students who are a part of the therapist's caseload receive services in an inclusive classroom setting alongside their peers, thus, allowing the therapist to serve multiple students during one time period within the LRE (least restrictive environment). In the long-run, this approach may be a more time efficient way to provide therapy services.

Benefits of co-teaching:

- expanded instructional options because of the combined expertise of the two professionals;

- improved program intensity because of a higher teacher-to-student ratio;

- enhanced educational continuity for students with special needs who are not pulled out of the classroom for services4;

- students without disabilities benefit from related service providers’ expertise. Students at-risk of delays, in essence, receive therapy services embedded in the inclusive classroom that may prevent delays. Bazyk and colleague found statistically significant improvements in fine motor and emergent literacy skills when the OT fully integrated services in a kindergarten curriculum.5

Examples of co-teaching content related to mental health:

- Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) content. With most states adopting SEL academic standards, school counselors, OTs, and SLPs might co-teach lessons related to developing a feeling vocabulary, recognizing feelings in others and being empathetic, and making responsible decisions (refer to www.casel.org);

- Mental health literacy. The school nurse and OT might team up to read stories related to mental health and lead discussions during the class reading time. Specifically, students can be taught about the signs of positive mental health and strategies for taking care of one’s mental health. Refer to Embedded Strategies and Moments for Mental Health.

- Interoception. The OT and health educator in an inclusive classroom can co-teach lessons on what interoception is and the importance of tuning into and responding to body signals related to anxiety, fatigue, and emotions (refer to www.kelly-mahler.com)

References:

1Cook, L., & Friend, M. (1995). Co-teaching: Guidelines for creating effective practices. Focus on Exceptional Children, 28(3), 1–16.

2Cahill, S., & Bazyk, S. (2019). School-Based Occupational Therapy. In Jane Clifford O’Brien & Health Kuhaneck (eds.). Case-Smith’s Occupational Therapy for Children & Adolescents (8th edition). Mosby.

3Kuypers, L. (2011). The zones of regulation: a curriculum designed to foster self-regulation and emotional control. San Jose: CA, Social Thinking Publishing Forum, The George Washington University.

4Silverman, F. (2011). Promoting inclusion with occupational therapy: A co-teaching model. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools and Early Intervention, 4, 100–107. doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2011.595308

5Bazyk, S., Goodman, G., Michaud, P., Papp, P., & Hawkins, E. (2009). Integration of occupational therapy services in a kindergarten curriculum: A look at the outcomes. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63, 160-171.Coaching is another strategy that can be used by related service providers committed to integrating services in natural school contexts throughout the day. Traditionally, related service providers have used consultation to help teachers apply therapy strategies in the classroom. Verbal or written information is shared by the therapist for the teacher to implement. Coaching differs in that the related service provider engages in shared work with the teacher in order to model strategies and guide the teacher in implementation.

Coaching to foster participation in school activities can be guided by the Occupational Performance Coaching (OPC) process.1 OPC involves three major components: emotional support, information exchange, and a structured process. Although originally developed to be applied with parents of children with disabilities, the basic elements may be used as a guide when working with teachers and other school-based personnel.

Coaching to foster participation in school activities can be guided by the Occupational Performance Coaching (OPC) process.1 OPC involves three major components: emotional support, information exchange, and a structured process. Although originally developed to be applied with parents of children with disabilities, the basic elements may be used as a guide when working with teachers and other school-based personnel.

Three main elements of coaching:

1) Emotional support is important during initial interactions in order to build a sense of partnership and trust. The first step in building trust with frontline workers is to tune-into their emotional needs and learn about their challenges. When working with cafeteria supervisors, for examples, it is important for the occupational therapist or other program facilitators to acknowledge their challenges and needs. Some of their biggest challenges, in our experience, includes dealing with noise levels in the cafeteria and managing challenging behaviors.2 In order to build trust, Interactions need to communicate, ‘I’m here to help support you in your work in order to make things better’. Five key ingredients to providing emotional support include:

- Active listening without judgement to validate the person’s experiences and feelings

- Empathize by demonstrating understanding and respect for the person’s experience (it must be difficult to get students’ attention when it’s so loud in the cafeteria)

- Reframe situations by offering alternative solutions to the problem (instead of asking students to eat in silence, let’s see if we can teach them how to control their speaking volume)

- Guide the person’s reflections and choices for action instead of giving directives

- Encouragement is important to acknowledge the person’s efforts and help them persist. Compliment the person on successes and improvements (Wow! I noticed the students lowered their voices when you used that hand signal! What a creative idea to put colorful conversation starters on each table!)

2) Information exchange is important to understand person’s perceptions of the problem and/or occupational performance expectations. For example, in the cafeteria program, a discussion about noise levels resulted in supervisors talking about their personal sensory preferences for and tolerance of noise. Some cafeteria supervisors did not mind loud cafeteria environments and were happy to see children talking with each other and having fun. Others struggled with being in a loud environment. Make sure to take time to listen to teachers, para-educators, recess supervisors ‘stories’ in order to identify how to make their jobs more manageable.

3) Implementing a plan of action. This component of coaching involves developing a clear sequence of steps including setting goals, exploring options, planning action, carrying out the plan, checking performance, and generalizing abilities. The therapist's ultimate goal is guided by the dual intention of improving children's participation and assisting frontline personnel in promoting successful participation and enjoyment. For the cafeteria program, an initial orientation session, embedded activities, and follow-up coaching were used to create a comfortable cafeteria for children with and without disabilities.

References:

Graham, F., Rodger, S., & Ziviani, J. (2010). Enabling occupational performance of children through coaching parents: Three case reports. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 30(1), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.3109/01942630903337536.

Bazyk, S., Demirjian, L., Horvath, F., & Doxsey, L. (2018). The Comfortable Cafeteria program for promoting student participation and enjoyment: An outcome study. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74 (3), 1-9, https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot2018.02379

Being able to socially interact and participate within a group is an important life skill!

Being able to socially interact and participate within a group is an important life skill!

The best way to teach these skills is within small group interventions. A multitude of skills can be taught and practiced in groups such as:

- how to be a good friend

- active listening

- expressing feelings appropriately

- how to work as a team

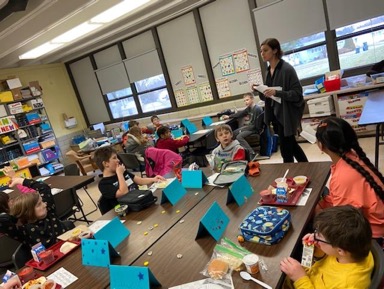

Providing therapy within small groups is an effective way to integrate services in natural school contexts. In addition to facilitating small groups during co-teaching in a classroom (as described above), small groups can be offered during lunch, recess, and after-school. Even a 20-minute recess or lunch period offers a rich opportunity to work with students in small groups.

What students can benefit from groups? The use of small group interventions can be an important strategy for providing both Tier 2 and 3 services.

Tier 3. For students with disabilities and/or mental health challenges (Tier 3), receiving therapy in a group allows them to interact with and learn from peers. There is strong research evidence supporting the effectiveness of small group interventions for improving social skills in students with mental health and social skills challenges.1 Students with higher level skills model positive interaction and functional skills to peers. We have also seen that students are often more effective in encouraging a reluctant peer to participate than an adult.

Tier 2. Students at-risk of mental health challenges, friendship issues, and social skills deficits can benefit from being included in small group interventions. High risk groups include students with disabilities (autism, ADHD, physical disabilities), those who are overweight/obese, and those who have experienced trauma, for example. Even if a student does not have an IEP goal focusing on mental health or friendship, small groups can be effective in promoting social participation with peers. In addition to including students on a therapist’s caseload, groups can also include those who are not. It is important for group facilitators to tune-into students who might benefit from participating in a particular group. For example, students who struggle with anxiety might benefit from a mindfulness/yoga recess group. Therapists can also ask teachers to recommend students in their classroom that they feel would benefit from participating in a group.

What school providers have entry-level skills in developing and facilitating groups?

- occupational therapists and OT assistants (skilled in facilitating activity-based groups addressing mental health)

- school counselors

- social workers

Benefits of group interventions:

Benefits of group interventions:

Therapists can work with more than one student on their caseload at a given time, opening up time for other tasks;

Therapy can benefit students who aren’t on their caseload, but demonstrate needs;

Groups can enhance life skills in settings where the skill is needed. For example, having a meaningful conversation is important during mealtimes which can be taught during lunch. Learning to play games can best be learned during recess or after-school.

Examples of small group interventions:

Lunch - Provide a ‘lunch bunch’ group targeting students who struggle to make and keep friends. Promote the development of conversation skills, mealtime manners, healthy eating, respecting differences, friendship skills, etc.

Recess - Provide recess groups targeting students who struggle to make friends and with limited play skills. Promote the development of teamwork, friendship skills, active play, etc. Use the groups to expose students to potential hobbies and interests (e.g. games, crafts).

Recess - Provide recess groups targeting students who struggle to make friends and with limited play skills. Promote the development of teamwork, friendship skills, active play, etc. Use the groups to expose students to potential hobbies and interests (e.g. games, crafts).

After-school - Provide groups targeting students with limited friends and out-of-school leisure. Promote exposure to and participation in a range of health leisure activities. Refer to the Making Leisure Matter initiative.

References: Bazyk, S. & Arbesman, M. (2013). Occupational Therapy Practice Guideline for Mental Health Promotion, Prevention, and Intervention for Children and Youth. Bethesda, MD: AOTA Press. Olson, L. (2011). Development and implementation of groups to foster social participation and mental health. In S. Bazyk (Ed.), Mental health promotion, prevention, and intervention with children and youth: A guiding framework for occupational therapy (pp. 95-116). Bethesda, MD: The American Occupational Therapy Association, Inc.

Everyone benefits from universal programs!

Everyone benefits from universal programs!

When related service providers implement universal programs, they share their knowledge and skills in a way that benefits all students, with and without disabilities and/or mental health challenges. In this way, schools 'get a bigger bang out of their therapy buck', reaping the benefits of having health professionals (OTs, SLPs, PTs) and mental health providers (school counselors, psychologists) in addition to teachers.

- OTs can apply knowledge of play, leisure, mealtimes, social participation, sensory processing, activities of daily living, health maintenance

- SLPs can apply knowledge of functional communication and social pragmatics

- PTs can apply knowledge of physical health, biomechanics, coordination, safe movement, and exercise

- School counselors and social workers can apply knowledge about mental health interventions and interpersonal relationships

- School nurses can apply knowledge about health and wellness and intervene with students who have injuries or health challenges

During a universal program, skilled therapists are able to tune-into the participation needs of students on their caseloads as well as all other students. Opportunities for this are available both in the classroom and elsewhere.

For example, during the Comfortable Cafeteria program, therapists can make a point to observe students who may be sitting alone or excluded, or those who might struggle with the sensory aspects of the cafeteria. During the Refreshing Recess program, therapists can tune into students who might be sensory-seekers or have difficulty with self-regulation.

Refer to the following Every Moment Counts universal programs:

Calm Moments Cards

Comfortable Cafeteria

Refreshing Recess

Making Leisure Matter

Remember this!

Students with disabilities do not attend school to receive related services; they receive services so they can attend and participate in school. (Giangreco, 2001)

Shifting to Integrated Services: The Process

The process for shifting from a pull-out to integrated model will vary depending on the school district and how related service providers are employed. In general, related service providers are either employed directly by the school district or educational service center or by a private practice company that places therapists in schools. The motivation to provide integrated versus pull-out therapy often starts at the top - with leaders who value and advocate for this type of service provision. Refer to the following sections for suggestions on how to shift to an inclusive classroom integrated model and success stories.

Integrated services help ensure that therapists become a part of the school's culture, that personnel and students understand therapists' distinct knowledge and scope of practice, and that therapists can positively impact students at the universal, targeted, and individualized levels.

Suggested Strategies for Moving Toward an Inclusive Classroom Integrated Service Model:

Suggested Strategies for Moving Toward an Inclusive Classroom Integrated Service Model:

1. Educate administrators and school personnel on why integrated services is best practice – refer to the section above on ‘Why’. Share the AOTA information sheet on Inclusion of Students with Disabilities.

2. Obtain school administrative support to free teachers and related service providers from their teaching/therapy schedules. Bazyk and colleagues1 found that when providing integrated services, time spent collaborating with the teacher and other personnel outweighed time spent in direct intervention by a 2 : 1 ratio.

3. Identify a time for planning and commit to collaboration over time. Strive to develop positive relationships with teachers, paraeducators, and other relevant stakeholders (e.g. SLP, school psychologist, PT, cafeteria supervisor, etc.). Commit to a collaborative style of interaction built on mutual trust, respect, and effective communication characterized by the equal status of all parties involved. Consider developing a community of practice (CoP) to enhance collective work and impact. A CoP is a group of people who are committed to a common cause, interact regularly, and share leadership and work for collective competence and impact.2

4. Learn about the unique classroom culture, the curriculum, and performance expectations. Therapists need to understand school district policies, curriculum, and the classroom practices of teachers to develop educationally relevant approaches to providing services in an inclusive classroom. Informally observe the physical, social, and emotional aspects of the environment (e.g., classroom layout, teacher-student interactions). Talk with the teacher about challenges and needs specific to your scope of practice. When working with students in a classroom, related service providers need to have a clear understanding of classroom expectations. This includes knowledge of classroom rules, routines, and dynamics and of the general education curriculum and special education adaptations. Each classroom teacher has unique teaching and classroom management styles. Intervention strategies conducted in the classroom that may be acceptable to one teacher may not be acceptable to another teacher; they may even be considered intrusive.

5. Offer inclusive classroom intervention strategies that fit the existing classroom structure and culture. For example, a teacher who values child-directed learning and hands-on learning centers may respond well to a therapist's suggestions for activities to be included in the learning centers. Another teacher who uses a strong teacher-directed classroom may prefer to engage in team-teaching activities with the therapist.

6. Provide information about your professional and full scope of practice using informal opportunities to share information (e.g., conversations in the hallway, one-page information briefs) and formal in-service education. Occupational therapists, for example, can describe the areas of function they can address beyond handwriting and sensorimotor processing, such as social participation, mental health, play, leisure, sleep/rest, and work.

7. Explore teacher preferences for integrated services. Be sensitive to the general education classroom routines and avoid disrupting the student's and the classroom schedule, if possible. Teachers may prefer to have therapist in the classroom at certain times or on certain days. These preferences should be negotiated with the teacher before intervention, and attempts should be made to schedule times for providing services to the student that coincide with targeted goal areas. For example, mental health literacy might be integrated into the student's language arts time.3

8. Consider integrating services during non-academic times of the school day, especially lunch and recess. Also, don't forget to integrate services in art, music, PE, and health education. These are critical times of the day for students to enjoy time with friends, eat lunch, engage in conversations, and have fun playing. These are also times when therapists can offer small group interventions (Tier 2) for students who struggle socially and/or who have difficulty participating due to functional limitations. Group participants can include students with and without disabilities and/or mental health challenges in order to foster inclusion. Lunch and recess periods also offer opportunities for therapists to provide universal services, such as the Refreshing Recess and Comfortable Cafeteria programs.

References: 1Bazyk, S., Goodman, G., Michaud, P., Papp, P., & Hawkins, E. (2009). Integration of occupational therapy services in a kindergarten curriculum: A look at the outcomes. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63, 160-171. 2Wenger, E., McDermott, R., & Snyder, W. (2002). Cultivating communities of practice: A guide to managing knowledge. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press. 3Cahill, S., & Bazyk, S. (2019). School-Based Occupational Therapy. In Jane Clifford O’Brien & Health Kuhaneck (eds.). Case-Smith’s Occupational Therapy for Children & Adolescents (8th edition). Mosby

Success Story: From pull-out to integrated service provision. How one school district made the transition

Success Story: From pull-out to integrated service provision. How one school district made the transition

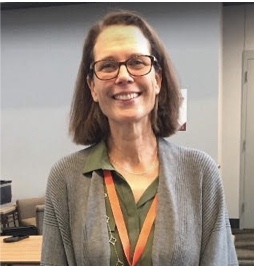

Occupational therapist: Carol Conway, MS, OTR/L

Hudson City Schools, Ohio

About the school district: The top ranked, high performing Midwestern suburban school district where I work has a reputation for academic excellence with 97% of our graduates attending four year colleges. Students receiving special education services make up 16% of the student population. Despite the fact that integrated services is considered best practice in schools, related services in this district reflected an outdated pull-out therapy model. Factors that  may have prevented the transition to integrated services and a more inclusive classroom include: 1) lack of knowledge about how to provide integrated therapy services; 2) a belief by some school staff and parents that pull-out therapy is most effective; and 3) a lack of planning time to change practice. Although some therapists made attempts to shift to an integrated service model, without the ability to meet and develop a unified plan, it was difficult to make significant changes.

may have prevented the transition to integrated services and a more inclusive classroom include: 1) lack of knowledge about how to provide integrated therapy services; 2) a belief by some school staff and parents that pull-out therapy is most effective; and 3) a lack of planning time to change practice. Although some therapists made attempts to shift to an integrated service model, without the ability to meet and develop a unified plan, it was difficult to make significant changes.

In the fall of 2011, with the assistance of an outside OT consultant from a local university, the district OTs (6) and PTs (2) made a commitment to working together to shift services to an integrated model. Before making changes, we met with the Director of Pupil Personnel to communicate the need for this work and to obtain buy-in. This was a critical first step, because her support throughout the change process was essential (e.g. to obtain permission to meet during school hours).

Here is a summary of what we did and the outcomes of our work:

Step 1: Getting Started

Step 1: Getting Started

Become knowledgeable about integrated services: what, why, how, and where. The OTs, PTs, and Director of Pupil Personnel met for an initial 2-hour meeting during which we reviewed the requirements of the law and evidence supporting integrated services. Time was spent discussing the need to shift services as well as barriers and supports. We decided to complete a time study of our services in order to obtain a baseline and to meet afterward to begin strategic planning.1

Complete a time study of therapy services. Two pieces of data were collected from the OTs and PTs: type of direct service (individual or group) and location of service (pull-out in therapy room or embedded in resource room, general education classroom, or ‘other’). ‘Other’ included any natural setting in the school including: playground, cafeteria, hallway, locker, restroom or the bus. Results of our initial time study indicated that the majority of our services were being delivered using pull-out therapy in isolated settings (75.5%). Therapy was integrated in the resource (special education) room 10.1% of the time, in the general education classroom 9.7% of the time, and ‘other’ 4.7% of the time. Direct services were provided individually 75.3% of the time and in groups 24.7% of the time. It was clear that our initial data supported the need for change in how related services were being delivered in our district.

Step 2: Warming up for change

Therapists began to explore opportunities for integrating services and brainstorm how to implement change. They also began to talk with relevant stakeholders (administrators, teachers, staff and parents) who were likely to support and pilot a more collaborative integrated model. The seeds of change where planted, mini trials of “push in” services where implemented and success stories where shared. The results of brainstorming, planning and mini-trials from the spring of 2012 led the district committing shifting to an integrated service model during the upcoming school year.

Step 3: Mobilize supports for action using a Community of Practice (CoP)

Because changing service provision to an integrated model affects all school personnel and parents, we decided to develop a Community of Practice (CoP) of relevant stakeholders to be a part of and assist in the change process. A CoP is a group of people who are committed to a common cause and interact regularly for collective competence and impact.2 A diverse group of stakeholders representing all district school buildings were invited to be a part of the CoP including: Director of Pupil Personnel (our direct supervisor), two district principals, two general education teachers, several special education teachers, a school psychologist, two parents of children with disabilities, the district parent mentor, a speech pathologist, and three paraprofessionals. During our first meeting (August), an overview of legislation requiring integrated services (i.e. LRE) and supporting research evidence was presented followed by open discussion. The group’s support of an integrated model was overwhelming positive. Ideas of how to generate change were discussed and the role of the CoP members was defined.

Shared leadership and collaborative work. During the first year of implementation four CoP meetings were held. One concern about shifting services was that parents and some school personnel might perceive integrated therapy as inferior to and ‘less than’ individual pull-out therapy and question administration about this change. Subsequently, it was decided that the first priority was to educate and communicate our message within the district and to the community in order to obtain ‘buy in’. Collectively, the CoP also decided to strategically communicate success stories of integrated services.

Step 4: Implementing change

Step 4: Implementing change

District therapists began discussing and implementing changes in service delivery within their individual educational teams at the start of the school year in 2012. By starting at the beginning of the year, therapists were able to schedule integrated programing more effectively. Therapists chose teams where they had established strong relationships and who they believed would be open to a more collaborative, integrated approach. Strategies to initiate change varied from building to building and were influenced by the age of the student as well as individual student needs. The district goal was to shift from 24.5% to at least 40% integrated services and inclusive classrooms during the 2012-2013 school year.

The most significant challenge for most therapists was establishing time to collaborate with teachers and other relevant school staff. Therapists often worked on multiple teams and needed multiple planning times. Finally, therapists needed to develop a new skill set which involved a role release from a traditional clinical model to a more collaborative, inclusive classroom co-teaching model.

Within individual buildings therapists embedded services at the Tier 1, 2 and 3 levels in collaboration with educational colleagues. The net results were overwhelmingly positive as therapists were increasingly welcomed into classrooms and other natural settings (e.g. art, music, PE). Word of success and student growth using integrated collaborative approaches spread among the faculty, administration, and parents resulting in expanding interest to replicate such strategies in more settings throughout the district.

Step 5: Celebrating outcomes

The original time study was repeated at the end of the school year (June 2013). Changes in place of service delivery were impressive. Integrated services shifted from 24.5% (2011) to 60.2% (2013) with 17.2% of services occurring in the general education classroom, 31.6% in the resource room, and 11.6% in other natural settings. Pull-out services in the therapy room decreased significantly from 75% down to 40%. The type of direct services also shifted to more time providing group services (44%, up from the original 24.7%) and less time providing individual services (55.8%, down from the original 75%). The success of the first year bolstered the interest and continued work toward integrated therapy. One year later (June 2014), integrated services grew to 70.3% with a steady decline in pull-out therapy.

We believe the following factors contributed to overall success: therapists' ability to reflect on practice and to be open to change; administrative buy in and support; development of a Community of Practice to foster collective learning and impact; and initiating change with educational team members where we had existing strong relationships.

Step 5: Commit to sustainability

What we have learned over the past 10 years, is that change takes time and a commitment from the whole team to shift to an integrated model. To sustain the provision of integrated services, it is helpful to have a handful of related service providers serve as champions to intentionally re-educate therapists and orient new personnel to integrating therapy in natural settings. This can be done by formal and informal professional development, modeling integrated services, and sharing success stories in school newsletters.

References:

1Cahill, S., & Bazyk, S. (2019). School-Based Occupational Therapy. In Jane Clifford O’Brien & Health Kuhaneck (eds.). Case-Smith’s Occupational Therapy for Children & Adolescents (8th edition). Mosby.

2Wenger, E., McDermott, R., & Snyder, W. (2002). Cultivating communities of practice: A guide to managing knowledge. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press. Rebecca Mohler, MS, OTR/L

Rebecca Mohler, MS, OTR/L

President, Sendero Therapies, Inc.

Becky’s vision: “At the initial development of the company, I wanted to address the need for school-based occupational therapy to enhance proper delivery of the educational model. It was also important to me that occupational therapy practitioners working in the schools felt supported and had a network and resource through Sendero Therapies, Inc.”

Celebrating over 20 years, Sendero Therapies, Inc. is a pediatric practice that employs over 40 occupational therapists (OTs), certified occupational therapy assistants (OTAs), speech-language pathologists (SLPs), physical therapists (PTs) and physical therapy assistants (PTAs). Sendero Therapies, Inc. serves school districts, charter schools, and private schools in Northeast Ohio.

Guiding framework: Integrating services within a multi-tiered framework guides therapists in order to address the academic and non-academic (e.g. lunch, recess) participation needs of students with and without disabilities and/or mental health challenges. Direct and indirect services are provided reflecting:

Tier 3: Individual therapy for student receiving special education

Tier 2: Targeted services for students at-risk of academic and participation challenges (small group prevention interventions)

Tier 1: Universal, whole classroom and school services focusing on participation and mental health promotion (e.g. Comfortable Cafeteria, Refreshing Recess)

How does Becky shape practice to reflect integrated services emphasizing academic success and health?

A critical part of Becky’s role is education and advocacy for ‘best practice’ in schools. This is an ongoing process. Education and advocacy of best practice must be done with:

- School district administrators

- Sendero-employed therapists

Initial and ongoing communication with school district administrators and potential employees is provided to educate them on Sendero’s mission and values. New school contracts are established and therapists hired based on a shared understanding of Sendero’s commitment to:

Initial and ongoing communication with school district administrators and potential employees is provided to educate them on Sendero’s mission and values. New school contracts are established and therapists hired based on a shared understanding of Sendero’s commitment to:

1) Therapists working as a team with all school personnel at their assigned schools. Therapists work to develop relationships and become a part of the school’s culture.

2) Services that reflect therapists’ full scope of practice. School administrators and personnel learn about OT, PT, and SLP’s scope of practice within an educational model. E.g. OTs address student’s participation in academics (e.g. handwriting, self-regulation) as well as daily living skills (e.g. eating lunch), social participation (e.g. friendships), play during recess, extracurricular leisure, and health maintenance.

3) The integration of services in the natural school context versus isolated therapy rooms. Educating employed therapists on how to integrate services throughout the school day (versus pull-out therapy) and ongoing coaching to ensure implementation is essential. This is done with ongoing continuing education and supervision.

4) A workload versus caseload model that supports universal and targeted services (e.g. implementing the Comfortable Cafeteria and Refreshing Recess programs) in addition to 1:1 interventions. Therapists are encouraged to provide services in non-academic settings (e.g. lunch, recess) in addition to the classroom and are paid for their planning and implementation of universal programs such as the Comfortable Cafeteria.

5) Evidence-based practice. Ongoing strategies to build capacity of therapists to develop new knowledge and skills are offered (e.g. continuing education courses, mentoring, and shared resources).

6) Innovation. Sendero therapists have been involved with the Every Moment Counts’ initiative since its inception in 2011. Becky has been a committed OT Change Leader in program development and research (co-developed the Refreshing Recess program), building capacity of Ohio OT/OTAs, and presenting nationally. She provides ongoing education and coaching to help therapists implement Every Moment Counts initiatives.

7) Clinical education of entry-level OT/OTA and PT/PTA students and volunteers planning to pursue OT or PT education. Sendero Therapies, Inc. has a long history of providing Practicum and Level 2 fieldwork/clinical experiences for students. More recently, OTD capstone students have also been accepted. Even during the pandemic with many schools providing virtual education, Becky has encouraged student education. Twelve students were supervised during the Fall and Spring school year (2020-2021). In order to ensure that therapists and students would have positive learning experiences, Becky developed a Pandemic FW Education Exploration & Innovation initiative. This demonstrates Sendero’s commitment to clinical education, service, and therapists’ professional growth and innovation.

Success Stories:

Cheri Harney, COTA, has contributed to the Making Leisure Matters initiative. In this capacity, she led an occupation-based breakfast leisure group with a group of siblings at-risk of mental health challenges whose mother was incarcerated. Cheri was also involved in the initial implementation of the Refreshing Recess program and provides mentoring and coaching to Sendero therapists planning to implement Tier 1 and 2  services.

services.

Ashleigh Spires, MOT, OTR/L, Jen McCallen, MOT, OTR/L, and Casey Kingsley, COTA/L have implemented the Comfortable Cafeteria program several times in their district. Most recently, they have implemented the program as a Tier 2 service with students who struggle with social challenges. General education peer helpers also participate in order to foster inclusion.

Making Connections and Learning Together (MCaLT)

Making Connections and Learning Together (MCaLT)

Developed by: Robin Kirschenbaum, OTD, OTR/L (2016)1

MCaLT is an occupational therapy (OT) developed program focusing on the development of social and emotional learning (SEL) and inclusion. It is designed to be embedded in integrated primary level classrooms (students with and without disabilities), especially in classrooms with students who have challenges in social participation and/or self-regulation. Specifically, students with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) may benefit from this program when in inclusive settings. MCaLT is a peer-mediated intervention program in which all students engage in learning activities to create and support a positive, caring, and respectful social emotional classroom environment. The interventions utilize selected children's literature, cooperative learning activities and lessons from The Zones of Regulation® curriculum.2 Key elements of the MCaLT program are the use of children's literature, visual supports such as posters, a classroom binder with child-friendly hand-outs and student generated work and collaborative efforts of the occupational therapist and general educator to support generalization of learned skills to everyday activities and routines.

The MCaLT e-Manual provides occupational therapy practitioners (OTPs) and other school personnel with guidelines, specific lessons, and resources to implement the program in elementary school classrooms. Teachers can use the materials to support carry over into daily class activities and routines. All the necessary materials are free and downloadable.

The MCaLT e-Manual provides occupational therapy practitioners (OTPs) and other school personnel with guidelines, specific lessons, and resources to implement the program in elementary school classrooms. Teachers can use the materials to support carry over into daily class activities and routines. All the necessary materials are free and downloadable.

Download the full MCaLT manual here

A key aspect of the MCaLT program is teaching all children about the importance of peace, love, and respect for everyone. Robin developed an activity to have children say the MCaLT affirmation along with physical gestures. In this way, children are an active participant in learning 'Peace, love, and respect for everyone'. Click on this link to view a 9 second video of Robin demonstrating the MCaLT affirmation.

Watch the video of Robin Kirschenbaum discussing MCaLT.

MCaLT Toolkit Materials:

Video of the MCaLT affirmation – peace, love, and respect for everyone

Orientation Power Point to introduce MCaLT to school personnel

Visual Task Schedule with icons

Think, Feel, Do Person Poster

Module 1, Lesson 4, DJLM posters

Module 1, Lesson 5, Taylor poster

Module 3, Lesson 1, Diagram of lungs

Module 4, Lesson 3, Assertiveness Bill of Rights

Module 4, Lesson 3, Passive-assertive-aggressive continuum

Suggested Children's Literature for MCaLT

References

1Kirschenbaum, R. (2016). Making Connections and Learning Together (MCaLT) e-Manual. Every Moment Counts.

2Kuypers, L.M. (2011). The Zones of Regulation: A curriculum designed to foster self-regulation and emotional control. San Jose, CA: Social Thinking Publishing.

“Brownie Busters”: An Occupation-Based Group for Children with Multiple Disabilities

Occupational therapist: Eileen Dixon, MS, OTR/L

Occupational therapist: Eileen Dixon, MS, OTR/L

Cleveland Municipal School District, Cleveland, Ohio

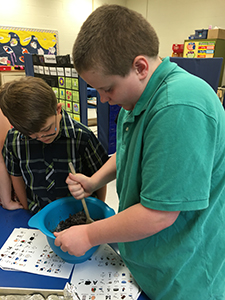

What? The Brownie Busters program was developed to integrate occupational therapy (OT) services within a special education classroom. Using a co-teaching model, the OT planned and led the program with the teacher and para-educators serving as helpers. The program consisted of six 1.5 hour groups that occurred over a 6-week period.

The Brownie Busters program was developed to: 1) provide a community-based functional curriculum for elementary students with multiple disabilities; 2) provide meaningful activities that would teach skills needed for future independent living and employment; and 3) encourage collaboration among school team members, including the teacher, teacher's assistant, occupational therapist, and parents.1,2,3

The Brownie Busters group involved having the students make and sell brownie-making kits to teachers, students, and staff at their school. Emphasis was on the development of independent living and work skills, such as:

The Brownie Busters group involved having the students make and sell brownie-making kits to teachers, students, and staff at their school. Emphasis was on the development of independent living and work skills, such as:

1. planning a work task

2. functional reading (reading labels and recipes)

3. safe community mobility (e.g. walking to the grocery shopping)

4. simple cooking and baking (measuring, pouring, and mixing ingredients)

5. using an oven

6. sanitary food handling (e.g. washing hands, wearing hairnets)

7. making and selling a product

Participants

Eight elementary students ages 9 to 12 years with multiple disabilities, including mild to moderate intellectual impairment and language delays.

Group Sessions

Group Sessions

The group sessions involved weekly discussions of basic work skills, a trip to the grocery store, making the brownie mixes, putting them in jars, decorating the jars, and selling them. Each session also involved clean up.

One must crack an egg in order to learn how to crack an egg!

Qualitative Research Findings

Qualitative research methods were used to explore the meaning of group participation from the children's perspective. Each of the eight group members were interviewed during weeks 2 and 6 of the program by the occupational therapist to explore the personal meaning of the group experience. Participant observations served as the second form of data and consisted of weekly observations of the group.

Based on a qualitative analysis of the interviews and participant observations, three themes unfolded: shopping, special ingredients, and doing everything. When asked what comes to mind or what they liked the most when they think of the groups, all the participants talked about walking to and shopping at the neighborhood grocery store, ingredients needed for the project, and doing the tasks necessary for making the brownie jars. By being actively involved in the shopping process, students learned first-hand about how to locate the baking ingredients needed for the brownies. The students began to take on the role of shoppers by looking for items needed for baking and using a shopping list. Students also learned about each special ingredient's unique properties by handling, measuring, and tasting it.

Based on a qualitative analysis of the interviews and participant observations, three themes unfolded: shopping, special ingredients, and doing everything. When asked what comes to mind or what they liked the most when they think of the groups, all the participants talked about walking to and shopping at the neighborhood grocery store, ingredients needed for the project, and doing the tasks necessary for making the brownie jars. By being actively involved in the shopping process, students learned first-hand about how to locate the baking ingredients needed for the brownies. The students began to take on the role of shoppers by looking for items needed for baking and using a shopping list. Students also learned about each special ingredient's unique properties by handling, measuring, and tasting it.

Finally, students expressed joy in doing everything and began to function like workers—doing the task, sharing, demonstrating care with the ingredients, using sanitary food handling, and preparing the jars to sell. Findings support the importance of occupation-based practice in fostering the link between doing and becoming.

1Dixon, E. (2006). The Meaning of an Occupational Therapy Work Group for Children with Multiple Disabilities: A Phenomenological Study. [Unpublished master’s project]. Cleveland State University. 2Kardos, M., & White, B. (2006). Evaluation options for secondary transition planning. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 60, 333–339. doi:10.5014/ajot.60.3.333 3Mankey, T. (2012). Educator's perceived role of occupational therapy in secondary transitions. Journal of Occupational Therapy in Schools and Early Intervention, 5, 105–113. doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2012.701974