Embedded Strategies

Jump to a Section

Before You Dive In

On Demand Webinar

Occupational Therapist practitioners share proven strategies for how to embed mental health promotion into everyday situations. Watch the webinar to see how interdisciplinary integrated services foster participation and health!

Downloadable Materials

10 Moments for Mental Health

(2-page summary sheet of embedded mental health strategies; click image to download)

10 Approaches Supporting School Mental Health (2-page summary sheet)

Mental Health literacy 1-page handouts

Coloring Sheets Mental Health Promotion

Mental Health literacy list of books and apps

Be Kind to Your Mind bookmark

Family Mental Health Toolkit

(5 information sheets)

Check it Out! Video Clips of Embedded Mental Health Strategies

Video #1: Embedded Mental Health Strategies - Small OT activity group focusing on mental health literacy (2 minutes)

Video #2: Embedded Mental Health Strategies - A school counselor, special education teacher, and occupational therapist discuss the benefits of the co-teaching model focusing (2.5 min.)

Video #3: Embedded Mental Health Strategies - An occupational therapist talks about integrating services in the classroom focusing on self-regulation and social-emotional learning. (3.5 minutes)

Introduction: Embedded Mental Health Strategies

Embed

(verb)

to place or set (something) firmly in something else

Embedded mental health strategies involves placing interactions and activities aimed at promoting positive mental health firmly into all aspects of the school day – in the classroom, lunchroom, hallways, restrooms, during recess, and after school. Why? Because every moment counts in a young person's life. Small moments can make big differences in how students feel about themselves, the people around them, and their school. Embedded mental health strategies don't necessarily require 'doing more', but 'doing differently.' School staff and students can learn how to interact with each other and engage in activities that have been found to help people be mentally healthy - to feel good emotionally and do well functionally (i.e. positive mental health), such as: engaging in enjoyable activities2, focusing on strengths 3, and effectively coping with stressors 4 to name a few.

Information shared in this part of the website has been developed to help all school personnel learn and apply practical embedded mental health strategies throughout the day to:

- Promote mental health and enhance mental health literacy (Tier 1, all students)

- Prevent mental health challenges (Tier 2, at-risk students); and

- Become aware of symptoms associated with mental health challenges and learn how to make accommodations and interact in ways to help reduce stress and enhance functioning (Tier 3).

Before delving into these materials, make sure to read information provided in Foundations on Positive Mental Health so that you have an understanding of: the mental health continuum, positive psychology, mental health literacy, and a public health approach to mental health.

Suggestion: Invite a diverse group of school personnel (teachers, OTs, school psychologists, para-educators, speech therapists, principals, parents) to read about positive mental health and embedded mental health strategies on this website. Meet to reflect on the information and discuss how the team will collaborate to implement mental health promotion strategies – in big and small ways!

1 Mirriam Webster Learner’s Dictionary. Definition of embed. Retrieved from http://www.learnersdictionary.com/definition/embed 2 Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 359, 1367-77. 3 Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness. New York: Free Press. 4 Catalano, R. F., Hawkins, D., Berglund, M. L., Pollard, J. A., & Arthur, M. W. (2002). Prevention science and positive youth development: Competitive or cooperative frameworks? Journal of Adolescent Health, 31, 230-239.

10 Moments for Mental Health

(evidence-based embedded mental health promotion strategies)

Small moments make big differences in how children and youth feel and function throughout the day! As a mental health promoter, know that 'every moment counts' during your interactions with all children and youth.

Be a mental health promoter! Read about the following 10 mental health promotion ideas and activities and think about how you can incorporate embedded mental health strategies into your interactions throughout school day. It may take a little thought as well as getting some of your 'creative' juices flowing, but making a difference in the life of even one young person will be worth your time!

Embedded mental health strategies can also help you improve your own mental health!

Remember this:

Small moments make BIG differences in how children feel and function.

Moments for Mental Health (embedded mental health strategies)

Connect with students in caring ways and encourage them to connect with each other! Make 'friendship' your business. The goal is for every student to have at least one good friend. Tune into their friendships during lunch and recess. Children who have at least one good friend are less likely to be bullied.

Connect with students in caring ways and encourage them to connect with each other! Make 'friendship' your business. The goal is for every student to have at least one good friend. Tune into their friendships during lunch and recess. Children who have at least one good friend are less likely to be bullied.

Be a friendship promoter! Why?

- People with strong social relationships are happier and healthier.

- Close relationships provide meaning, support and a sense of belonging.

- Connecting with others, whether this is with students and/or other school staff, is at the heart of feeling good emotionally and happy – for you and for them.1,2

What helps people connect?

- Doing enjoyable activities together

- Talking together and feeling understood

- Being supportive with each other1

Try these simple embedded mental health strategies to connect on a daily basis:

- Make sure to stand in the hallway, smile and greet students by name.

- Remember to approach students at THEIR eye level, and look them in the eye when you speak to them.

- Simple expressions of genuine care can make ALL the difference in the life of a student - so remember to ask "How are you doing?" and LISTEN to the response!

- Take an interest in the life of children and youth you interact with. Ask, "How was your weekend?" "What did you do?" Tune into and encourage participation in healthy hobbies and interests.

- If a student looks upset or unhappy, check it out by asking 'You seem down, are you doing OK? Do you want to talk about it?" Take the time to listen.

- Model inclusion and acceptance of differences in people and their abilities. Make a point to include others, especially students who struggle to 'fit in'. "Hey Sarah, why don't you join us (e.g. in this recess game, group activity, or lunch table)?"

- Take the first five minutes of class to engage your students in casual conversation - to ask them about their day and what they do out of school. This is a great way to learn about students' interests and life out of school.

- Attend extra-curricular activities when you can. According to high school teacher, Nick Provenzano3, 'It's important to take an interest in the things students love if you want them to take an interest in what you love."

- Arrange to have some 'open door' times for students to pop in and talk. "For the students that stop by, I know it means the world to them to have an adult that will listen and be there when they need it."3

1 Ten Keys to Happier Living. http://www.actionforhappiness.org/10-keys-to-happier-living 2 Huppert, F.A. (2008). Psychological wellbeing: Evidence regarding its causes and consequences. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-being, 1(2), 137-164. doi:10.1111/j.1758-0854.2009.01008.x 3 Provenzano, N. (2014). 3 ways to make meaningful connections with students. Edutopia. http://www.edutopia.org/blog/make-meaningful-connections-with-students-nick-provenzano

Always assume the best about your students. Focus on their character STRENGTHS.

Always assume the best about your students. Focus on their character STRENGTHS.

Most adults think about 'strengths' as skills (e.g. athletic, verbal, social) or abilities (e.g. academic) that people are generally born with. Children and youth are often evaluated on their skills and abilities. Such evaluations only give a partial picture of the student's 'strengths'. As, or more important, are a person's unique character strengths – morally desirable traits such as kindness, creativity, courage, persistence, humor, and humility to name a few.3

Identify and nurture CHARACTER STRENGTHS! Recent evidence suggests that recognizing and using one's unique character strengths can help promote happiness and mental well-being – and decrease depression and anxiety.1 As adults working with children and youth, incorporating embedded mental health strategies can mean making a point to help them notice, value, and use their strengths in their everyday lives.

Certain character strengths such as hope, kindness, self-control, sociability and perspective have found to be protective factors in the negative effects of trauma and stress.2 Gratitude, optimism, enthusiasm, curiosity and love have been found to be important characteristics associated with positive mental health.2 Make a point to foster these in your everyday interactions with young people.

Simple embedded mental health strategies:

- Begin and end every conversation about a student by commenting on the child’s character strength. E.g. Julie is always willing to help; John is curious and full of energy; Curtis is creative.

- Know your strengths, be proud of them and use them daily. E.g. “I’m kind, sociable, persistent and love learning.” Being aware of our own strengths helps us be aware of strengths in the children around us.4

- Help children begin to identify their own character strengths and engage in activities that allow them to use them on a regular basis. E.g. For students who are nurturing, have them water the plants in the classroom; have creative students help design a bulletin board

- Have students journal or write about their unique character strengths and how they use them in everyday life. Promote sharing within small groups or the classroom so that students become aware of and celebrate each other’s strengths.

The most important character strengths for emotional wellbeing and happiness are gratitude, optimism, enthusiasm, curiosity and love.2

Image from Blair Turner (2014). End of year activity: Class Compliments. Free download on Teachers Pay Teachers.

1Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York: Free Press. 2 Park, N. & Peterson, C. (2008). Positive psychology and character strengths: Application to strength-based school counseling. Professional School Counseling, 12(2), 85-92. 3 Turner, B. End of the year class compliments. (free download) Teachers pay teachers. 4 Hands on Scotland. (2013). Character strengths.

Help Students do What They Love

"Human lives are governed by the desire to experience joy." Susan Engel1

Just like exercise is important for our physical health, experiencing positive emotions like joy, gratitude, inspiration and pride are important for taking care of our mental health.2

Just like exercise is important for our physical health, experiencing positive emotions like joy, gratitude, inspiration and pride are important for taking care of our mental health.2

How? As a mental health promoter, you can incorporate embedded mental health strategies by creating experiences that bring about positive emotions during the day (classroom, cafeteria, recess, & after-school). Help students explore and find activities that they love to do whether it is reading, math, helping others, art, music, or being physically active! When people engage in what they love to do, they feel good emotionally.

Why? Experiencing positive emotions on a regular basis has been shown to.2,3

- promote an 'upward spiral' of feeling good

- reduce negative feelings

- build resilience in the face of challenges

- increase the desire to participate more in the enjoyable activity and master it.

In addition to joy, there are many other positive emotions that help us feel good emotionally. Help young people recognize and experience these!

Small moments can make big differences in how children feel and function! Moments of positive emotions can be subtle or fleeting, but can be powerful 'nutrients' in helping young people be mentally healthy. Young people need a lot of these positive moments throughout the day to help them thrive.2 How much is enough? Overall, people need to experience more positive emotions than negative ones in a 3-to-1 ratio throughout the day.2

Simple embedded mental health strategies:

Observe the children/youth that you have close contact with. For each person, ask yourself, 'does he/she experience more positive emotions vs. negative emotions throughout the day'? What is their positivity ratio? Aim for a 3 to 1 ratio of positive to negative emotions. Reach out to those who experience more negative emotions and come up with ways to increase their positive emotions.

Observe the children/youth that you have close contact with. For each person, ask yourself, 'does he/she experience more positive emotions vs. negative emotions throughout the day'? What is their positivity ratio? Aim for a 3 to 1 ratio of positive to negative emotions. Reach out to those who experience more negative emotions and come up with ways to increase their positive emotions.- Help create experiences in the classroom and other school environments that bring about positive emotions. Think about implementing the Comfortable Cafeteria or Refreshing Recess programs to help children/youth enjoy lunch and recess.

- Help children/youth identify activities that result in joy or other positive emotions and encourage them to do these activities when they are not feeling well emotionally.

1 Engel, S. (2015). Joy: A subject schools lack. The Atlantic. http://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2015/01/joy-the-subject-schools-lack/384800/ 2 Fredrickson, B. L. (2009). Positivity: Groundbreaking research reveals how to embrace the hidden strength of positive emotions, overcome negativity, and thrive. New York: Crown Publishing Group. 3 Cohn, M. A., Fredrickson, B. L., Brown, S. L., Mikels, J. A., & Conway, A. M. (2009). Happiness unpacked: Positive emotions increase life satisfaction by building resilience. Emotion, 9(3), 361−368.

Make 'positive mental health' a part of everyday conversations. Use the words 'mental health'.

One way to increase awareness of mental health, is to make a point to talk about it in positive and meaningful ways throughout the day – either with groups of students or individually. Talking about mental health is one of our embedded mental health strategies that can promote mental health literacy – by helping all students and adults develop a working knowledge of positive mental health as well the signs of mental illness.1,2 Mental health is everyone's business.3

One way to increase awareness of mental health, is to make a point to talk about it in positive and meaningful ways throughout the day – either with groups of students or individually. Talking about mental health is one of our embedded mental health strategies that can promote mental health literacy – by helping all students and adults develop a working knowledge of positive mental health as well the signs of mental illness.1,2 Mental health is everyone's business.3

Think about creative ways to teach all children and youth about the four characteristics associated with positive mental health3 and ways to promote feeling good emotionally:

- Positive emotions – feeling happy (create academic and non-academic experiences that promote enjoyable participation)

- Positive psychological and social functioning – feeling good about oneself (e.g. aware of strengths); getting along with others; having at least 1-2 good friends

- Engaging in productive activities – doing well in everyday activities (school, play/leisure, rest)

- Coping with life stressors – having strategies for dealing with life challenges (e.g. relaxation strategies, thinking positive, etc.)

Make a point to emphasize that taking care of one's mental health is as important as taking care of one's physical health!

Simple embedded mental health strategies:

Use the words 'positive mental health' or 'mental well-being' when opportunities arise throughout the day. Give specific examples of what students and adults can do on a daily basis to take care of their mental health, such as: getting enough sleep, eating a healthy diet, exercising, and doing an enjoyable activity. Example: "It looks like everyone enjoyed reading that book today. Doing things that we enjoy is good for our mental health!"

Use the words 'positive mental health' or 'mental well-being' when opportunities arise throughout the day. Give specific examples of what students and adults can do on a daily basis to take care of their mental health, such as: getting enough sleep, eating a healthy diet, exercising, and doing an enjoyable activity. Example: "It looks like everyone enjoyed reading that book today. Doing things that we enjoy is good for our mental health!"- Have students visit and use materials on reputable websites to learn about positive mental health based on positive psychology, such as the 'Action for Happiness' website. Students can read about each of the 10 Actions for Happiness and the research that supports each action.

- Print out posters focusing on positive mental health and happiness and hang them throughout the school. See our Every Moment Counts posters – Be Kind to Your Mind.

- Embedded mental health strategies can happen when you're reading books in class. Make it a point to talk about how the characters' did things to take care of their mental health such as: talking about feelings, doing healthy and enjoyable activities, and being kind to others. Also tune into ways in which they demonstrated positive coping strategies, such as thinking positive and doing calming strategies (e.g. yoga, deep breathing).

1 Barry, M. M., & Jenkins, R. (2007). Implementing mental health promotion. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. 2 Jorm, A.F., Korten, A.E. , Jacomb, P.A., Christensen, H., Rodgers, B. & Pollitt, P. (1997). "Mental health literacy": A survey of the public's ability to recognize mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Medical Journal of Australia, 166, 182-186. 3 Weare, K. & Wolfgang, M. (2005). What do we know about promoting mental health through schools? Promotion & Education, Vol. XII, No. 3-4, 118-122. 4 Keyes, C. L. (2007). Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: A complementary strategy for improving national mental health. American Psychologist, 62, 95-108.

Helpful website: 'BeYou'. Be You, an Australian initiative, provides educators with information and resources for helping children and youth achieve their best possible mental health.

Helpful website: 'BeYou'. Be You, an Australian initiative, provides educators with information and resources for helping children and youth achieve their best possible mental health.

Look for opportunities to help students move throughout the school day.

There is a lot of strong evidence to support the brain–body connection when it comes to movement. In addition to promoting physical health, getting children and youth to move and be active throughout the day – even in short doses – promotes learning and mental health! In order to help children want to be physically active, it's important to make the activities FUN!

There is a lot of strong evidence to support the brain–body connection when it comes to movement. In addition to promoting physical health, getting children and youth to move and be active throughout the day – even in short doses – promotes learning and mental health! In order to help children want to be physically active, it's important to make the activities FUN!

Physical activity and learning: Short, classroom-based physical activity breaks have been shown to increase attention and on-task behavior.1,2 A majority of studies have found a positive association between physical activity breaks and cognitive skills, attitudes, and academic behavior.3,4 In addition to using embedded mental health strategies that incorporate movement in the classroom, make sure that students have opportunities to participate in physical education and engage in enjoyable active play during recess and after-school.

Physical activity and mental health: Physical activity and exercise have both short-term and long-term effects on mental health.5,6 Usually within five minute s of moderate exercise such as walking, there is positive effect on mood. In addition to helping people feel good emotionally, moderate-intensity exercise on a regular basis can help to reduce and prevent anxiety and depression.7

Simple embedded mental health strategies:

Be creative in thinking of and implementing short (2-5 minute) activity breaks during classroom learning – especially when students seem to have low energy/attention or, when they seem to be fidgety and needing movement. Example: For elementary students, pair students and have them 'arm wrestle' or 'thumb wrestle' for 3 minutes; have students perform one yoga pose; etc.

Be creative in thinking of and implementing short (2-5 minute) activity breaks during classroom learning – especially when students seem to have low energy/attention or, when they seem to be fidgety and needing movement. Example: For elementary students, pair students and have them 'arm wrestle' or 'thumb wrestle' for 3 minutes; have students perform one yoga pose; etc.- Visit educator Bevin Reinen's website, 'Teach, Train, Love' for 'Brain Break' music for dance clips. Use a Smart board or computer & projector to play one of the 2-3 minute dancing to music breaks. Have students get up, dance and have fun. These are appropriate for younger grades.

- Download the free poster, Roll Some Brain Breaks, from Your Therapy Source website. Use this poster and some dice to have children engage in upper and lower body movement.

- Consider using The Drive Thru Menus for Attention and Strength Posters (Teri Bowen-Irish, OTR/L) in your classroom with elementary school students. Each poster consists of a menu of 10 short exercises that can be embedded throughout the day. A Leader’s Manual provides complete instructions for implementing each activity. Available for purchase from Therapro.

1 Janssen, M., Chinapaw, M. J. M., Rouh, S. P., Toussaint, H. M., van Mechelen, W., & Verhagen, E. A. L. M. (2014). A short physical activity break from cognitive tasks increases selective attention in primary school children aged 10-11. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 7, 129-134. 2 Kibbe, D. L., et al. (2011). Ten years of TAKE 10®: Integrating physical activity with academic concepts in elementary school classrooms. Preventive Medicine, 52, 543-550. 3 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010). The Association Between School Based Physical Activity, Including Physical Education, and Academic Performance. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA. http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/health_and_academics/pdf/pa-pe_paper.pdf 4 Howie, E. K., Beets, M. W., & Pate, R. R. (2014). Acute classroom exercise breaks improve on-task behavior in 4th and 5th grade students: A dose – response. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 7, 65-71. 5 Weir, K. (2011). The exercise effect. Monitor on Psychology, 42(11), p. 48. http://www.apa.org/monitor/2011/12/exercise.aspx. 6 Peluso, M. A., & Andrade, L. H. (2005). Physical activity and mental health: The association between exercise and mood. Clinics, 60, 61-70. 7 Otto, M. W., & Smits, J. A. (2011). Exercise for Mood and Anxiety: Proven Strategies for Overcoming Depression and Enhancing Well-being. Oxford University Press. ISBN: 978-0-19-979100-2.

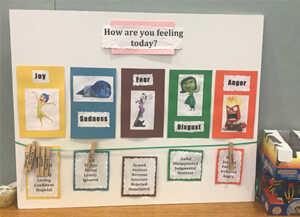

Children and youth enjoy talking about their feelings.1

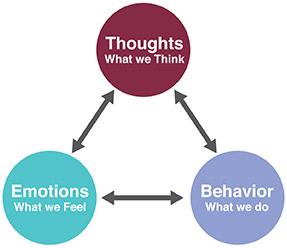

Make a point to stop and ask children and youth "How are you feeling?" ... and take time to listen to what they have to say. After all, feelings and emotions play an important role in shaping a person's behavior, interactions with others and concentration. In addition, when we take the time to ask about feelings, we are communicating that we care.

Make a point to stop and ask children and youth "How are you feeling?" ... and take time to listen to what they have to say. After all, feelings and emotions play an important role in shaping a person's behavior, interactions with others and concentration. In addition, when we take the time to ask about feelings, we are communicating that we care.

Why?

Emotional literacy is the ability to identify, understand and respond to emotions in oneself and others in a healthy way.2 Children who have a strong foundation in emotional literacy are mentally healthier, enjoy positive relationships and do better academically.

Teaching children to recognize, label and talk about their feelings is one of the core competencies of social and emotional learning (SEL) (see www.casel.org). Currently, all 50 states have preschool SEL standards and many states have SEL integrated in their academic standards.3 Embedded mental health strategies that foster SEL help children recognize feelings, control impulses and develop important skills for developing and maintaining healthy relationships.

How?

The Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (CASAL) and the Center on the Social and Emotional Foundations for Early Learning (CSEFEL) provide a wealth of user-friendly materials for school personnel and families on how to promote social and emotional learning – including how to help children talk about their feelings.4

Simple embedded mental health strategies:

- Teach a feeling vocabulary using a variety of embedded mental health strategies throughout the day using games, craft activities, songs and storybooks that focus on feelings.

Use a 'Feeling Continuum' activity to help children and youth reflect on how what they 'do' impacts how they 'feel'. Develop a poster or handout with a feeling continuum from angry/sad to joyful/happy (see example). Have them identify their feeling at the beginning of an activity and then reflect on their feeling after the activity. They will learn that doing something they enjoy, can help them 'feel good' emotionally.

Use a 'Feeling Continuum' activity to help children and youth reflect on how what they 'do' impacts how they 'feel'. Develop a poster or handout with a feeling continuum from angry/sad to joyful/happy (see example). Have them identify their feeling at the beginning of an activity and then reflect on their feeling after the activity. They will learn that doing something they enjoy, can help them 'feel good' emotionally.- Embed feeling activities into language arts, art and handwriting instruction. Use coloring and handwriting sheets developed for Every Moment Counts (see downloadable on left bar). Use color to help students learn about emotions.

- Teach feeling words and a range of intensity using a color wheel. Use the do2learn interactive emotion color wheel to help children learn feeling words, a picture of the feeling, and definition.

- Observe children's facial expression, body language, and tone of voice in order to help label their feelings based on your observations (e.g. "You seem a bit discouraged", "You look excited about going to recess").

- Read books that focus on characters who experience different feelings and talk about it afterwards. Pose questions to foster reflection on how to verbalize and manage emotions such as, "What do you think he was feelings?"; "What do you think she should do?". Suggested reading lists: For younger children, see Vanderbilt's CSEFEL comprehensive list of books by topics such as 'being a friends' to happy, sad, and scared feelings; for middle school students, see Carnegie Library's book list which provides books by topics such as racial representation and LGBTQ.

- Encourage students to tune-into other's feelings and respond with empathy.

- Express your own feelings out loud (e.g. 'that was frustrating for me') and demonstrate positive ways for dealing with feelings (e.g. 'I better take a deep breath').

- Teach students about their feelings and how to regulate their emotional state using The Zones of Regulation (Kuypers, 2011). Lessons and learning activities are designed to help students recognize their Zone (moods/alertness) and use strategies (sensory supports, calming techniques) to regulate their Zone in order to help them learn and interact effectively with others. This curriculum can be used by an interdisciplinary team and be embedded into a general or special education curriculum.

References: 1 Bazyk, S., & Bazyk, J. (2009). The meaning of occupational therapy groups for low-income youth: A phenomenological study. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 6, 69-80. 2 Joseph, G., Strain, P., & Ostrosky, M. M. (2005). Fostering emotional literacy in youth children: Labeling emotions – What Works Briefs #21. Center on the Social and Emotional Foundations for Early Learning (CSEFEL) (2009). 3 Durlak, J. A., Domitrovich, C. E., Weissberg, R. P., & Gullotta, T. P. (Eds.) (2015). Handbook of Social and Emotional Learning: Research and Practice. Guilford Press. 4 CSEFEL. Teaching your child to: Identify and express emotions.

Help students manage stress and experience emotional well-being.

All children and youth experience stress to varying degrees as a result of situational challenges (e.g. taking a test, entering a noisy environment, being teased, completing a difficult assignment, etc.). Situations that may seem manageable for an adult can be stressful for a young person depending on their developmental and emotional skills and abilities. Feeling stressed and anxious can negatively impact student learning (e.g. difficulty concentrating) and everyday functioning (sleeping, eating, and socializing). Chronic and intense stress may lead to anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem.

Why?

Learning how to cope with stressful situations and everyday challenges is an important life skill for all children and youth. Relaxation, yoga and mindfulness approaches are found to be promising practices in school settings for improving coping abilities and reducing anxiety.1,2,3 Such practices help students 'step back' from stressful situations by teaching them how to purposefully and non-judgmentally 'be in the moment'.4 Kabat-Zinn (2003) suggests that mindfulness helps calm and clear the mind and help focus attention.5 Embedding relaxation strategies may also reduce noise levels and increase concentration.6

How?

Consider embedding whole-class and/or whole school mindfulness strategies during transitions or before tests. These activities can be as short as 1-2 minutes or as long as 5-10 minutes. Important calming strategies include: deep breathing, yoga, short meditations, sensory strategies, creative arts activities, and time spent in green spaces.

Refer to the Calm Moments Cards, one of Every Moment Counts initiatives. These 17 cards provide thinking, calming & focusing, and sensory strategies and activities for reducing stress and fostering emotional well-being. Each card addresses a possible situational stressor (e.g. taking a test, starting a project). The Appendices provide activity templates and yoga poses. All of these materials are free and downloadable.

Simple embedded mental health strategies and user-friendly resources:

Deep breathing – There are many creative ways to teach deep breathing, such as 'bumble bee breathing'.7 It is important to have children repeat the deep breathing 3-5 times. Most instructions call for taking a slow breath in for about 4 seconds, holding the breath for 4-6 seconds, exhaling slowly through the mouth for 4-5 seconds, waiting 2-3 seconds and then, repeating several times. Consider using visualizations to teach deep breathing.

Yoga/movement stretches – Have students stop and do a yoga pose. Suggested program: Yoga4classrooms Card Deck and training programs

Calm Classroom program. Thirty-second to 3-minute strategies are used during normal school transitions to help students develop self-awareness, mental focus, and inner calm. Since 2008, this research-based curriculum has been implemented extensively throughout Chicago Public Schools. Learn about this program at the Calm Classroom Website.

Deep pressure (weighted lap pad, hand massage or self-hug) and other sensory strategies may be calming. See The Kid's Guide to Staying Awesome and in Control: Simple Stuff to Help Children Regulate Their Emotions and Senses (Brukner, 2014).

Embedded classroom strategies. Consider using The Drive Thru Menus for Relaxation and Stress Busters Posters (Teri Bowen-Irish, OTR/L) in your classroom to incorporate embedded mental health strategies with elementary school students. Each poster consists of a menu of 10 short exercises that can be embedded throughout the day. A Leader's Manual provides complete instructions for implementing each activity. Available for purchase from Therapro.

1 Bazyk, S., & Arbesman, M. (2013). Occupational therapy practice guidelines for mental health promotion, prevention and intervention with children and youth. AOTA Press. 2 Zoogman, S., Goldberg, S. B., Hoyt, W. T., & Miller, L. (2014). Mindfulness interventions with youth: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness. doi: 10.1007/s12671-013-0260-4 3 Wall, R. B. (2005). Tai chi and mindfulness-based stress reduction in a Boston public middle school. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 19(4), 230-237. 4 Rempel, K. D. (2012). Mindfulness for children and youth: A review of the literature with an argument for school-based implementation. Canadian Journal of Counseling and Psychotherapy, 46(3), 201-220. 5 Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. doi:10.1093/clipsy/bpg016 6 Norlander, T., Moas, L., & Archer, T. (2005). Noise and stress in primary and secondary school children: Noise reduction and increased concentration ability through a short but regular exercise and relaxation program. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 16(1), 91-99. 7Your Therapy Source. Breathing Breaks Deep Breathing Exercises. 16 cards available for purchase.

Promote Positive Self-Talk

Sometimes changing how we think, helps to change how we feel and behave. People who think positive tend to be happier, healthier and cope better during challenging times – but it's important to be a 'realistic optimist'.1 It's not realistic to pretend that everything is fine during difficult times. Being a realistic optimist requires being able to put situations in perspective by using thinking skills to help develop a positive outlook

Sometimes changing how we think, helps to change how we feel and behave. People who think positive tend to be happier, healthier and cope better during challenging times – but it's important to be a 'realistic optimist'.1 It's not realistic to pretend that everything is fine during difficult times. Being a realistic optimist requires being able to put situations in perspective by using thinking skills to help develop a positive outlook

How?

Share positive affirmations verbally and in print. The use if positive affirmations is a thinking strategy that can change our thoughts and how we feel. Positive new beliefs can be strengthened through repetition. Encourage students to repeat an affirmation during stressful times (e.g. I am going to do my best on this test). By changing our thoughts, we can change our life experiences. Positive thinking is linked to both psychological and physiological benefits such as stress reduction.1 Activity suggestions: Cut up affirmations from old calendars or downloaded from the internet. Fold them, put them in a decorated box, and have students pick one every morning at the start of the day to keep at their desk. Have students complete a coloring sheet with a positive affirmation or word.

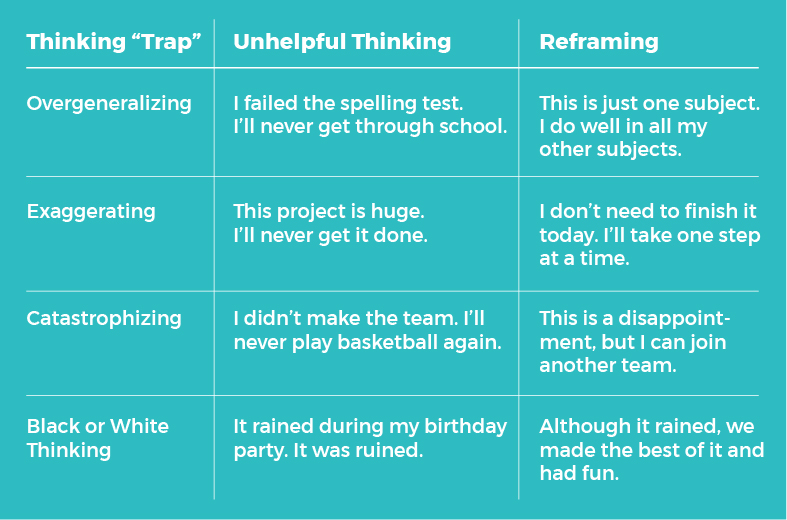

Share positive affirmations verbally and in print. The use if positive affirmations is a thinking strategy that can change our thoughts and how we feel. Positive new beliefs can be strengthened through repetition. Encourage students to repeat an affirmation during stressful times (e.g. I am going to do my best on this test). By changing our thoughts, we can change our life experiences. Positive thinking is linked to both psychological and physiological benefits such as stress reduction.1 Activity suggestions: Cut up affirmations from old calendars or downloaded from the internet. Fold them, put them in a decorated box, and have students pick one every morning at the start of the day to keep at their desk. Have students complete a coloring sheet with a positive affirmation or word.- Pay attention to 'self-talk' and recognize negative thinking 'traps'. Self-talk are the thoughts we say to ourselves throughout the day. It's important to identify 'thinking traps' – or faulty thinking – because such thoughts can lead to feeling sad, anxious or angry.2 Ask the young person to share what they are thinking – and listen nonjudgmentally.

- Help the young person develop 'realistic thinking' and 'reframe the situation'. This means thinking about all aspects of the situation in a balanced way – identifying both the negative and positive aspects of the situation.3 This helps to balance out the negative thoughts with positive ones leading to more positive feelings (calm, satisfied). Say something like, 'I can see why you might think that, but maybe we can think of the situation in another way.'

- Encourage gratitude – an appreciation of life and the moment. Cultivate optimism. Help the young person think about one or two good things happening at that moment – being mindful of what can be seen, heard or felt that is positive. Taking time to 'count our blessings' on a daily basis, either by writing or saying them can improve mental and physical health and feelings of happiness.4 Let's think of 1-2 things we're grateful for right now. (e.g. 'I have good friends; I'm healthy; I love my dog') Help students savor life experiences. 'Let's enjoy seeing the sun shine today. Make sure to enjoy your time outside at recess!'

- Look for opportunities to learn from the situation. Help young people view difficult situations as a challenge to overcome and opportunities to learn and become more resilient. Facing this challenge will help me know what to do the next time.

Simple strategies and user-friendly resources:

- Refer to the Calm Moments Cards for thinking strategies and activities. Positive affirmations are provided, such as "I know this material. I studied hard", or, "I have all that I need to make this a great day.".

- Complete the Thinking Strategies lessons from The Zones of Regulation (Kuypers, 2011).5 Lessons include worksheets and activities that can be embedded into language arts learning. Consider having your occupational therapist, school counselor, or speech therapist co-teach these classes.

- Size of the Problem Thinking Strategy Activity. (p. 122) This lesson helps students think about whether problems are 'big', 'medium', or 'little' and how such problems affect people around them.

- Inner Coach vs. Inner Critic Thinking Strategy Activity. This lesson (including worksheets & activities) helps students identify negative self-talk (inner critic) and develop positive thinking (inner coach).

- Superflex© vs. Rock Brain© Thinking Strategy Activity.6 (p. 131) This lesson helps students learn about rigid thinking (rock brain, getting stuck on a negative idea) and flexible thinking (superflex thinking, being able to consider different points of view).

- After reading stories in class, have students identify characters who demonstrated being in a negative thinking trap. Have the students reframe the situation and identify realistic thoughts, or a balanced view. Talk about what the character might learn from the situation.

- As an adult role model, demonstrate how you reframe situations by talking about positive and negative aspects of what happened. Show students how you remain optimistic! e.g. 'I am a bit flustered because I was in a small fender-bender accident this morning. This is upsetting, but I'm grateful that no one was hurt.'

- Look for ways to promote optimism and gratitude throughout the day. For language arts or handwriting practice, have them write a gratitude journal or a thank you note to a family member or friend. Help students express gratitude verbally to each other.

1 Cherry, K. (2019). Understanding the psychology of positive thinking. Very Well Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com 2 Actions for Happiness. Action 31: Be positive but stay realistic. Retrieved from http://www.actionforhappiness.org/take-action/be-positive-but-stay-realistic 3 Tartakovsky, M. (2015). 3 Handy Ways to Help Your Child Overcome Negative Thinking. World of Psychology. Psych Central. 4 Lyubomirsky, S. (2007). The HOW of happiness: A new approach to getting the life you want. London: Penguin Books LTD. 5 Kuypers, L. (2011). The Zones of Regulation. Social Thinking Publishing. This curriculum can be used by an interdisciplinary team. http://www.zonesofregulation.com/ 6 Madrigal, S., & Winner, M. G. (2008). Superflex: a superhero social thinking curriculum. San Jose, CA: Social Thinking Publishing.

Encourage Thoughtfullness and Caring

"Be kind whenever possible, it's always possible." - Dalai Lama

"Be kind whenever possible, it's always possible." - Dalai Lama

Being kind to others increases levels of happiness in others as well as our own feelings of happiness.1,2,3 Kindness is contagious! An act of kindness often results in more acts of kindness, making our schools and communities nicer places to live in.

Why?

There are multiple other benefits to promoting kindness. Acts of kindness, help:

- build a sense of cooperation, trust and safety in our schools and communities

- help us connect with others which, in turn, provide more support for ourselves

- help us see ourselves in a positive light – as being compassionate and caring

- help us be seen as more likable resulting in having more friends3,4

Kindness defined: According to Random Acts of Kindness, kindness means "being friendly, generous or considerate to ourselves and others through words and actions."5

What counts as kindness?

Kindness is any act of genuine care or thoughtfulness including:

Small, spontaneous acts that may take only a brief moment and that doesn't cost anything. Examples: smile, hold a door for someone, give a compliment to a friend, sit by someone who is alone at lunch, make someone new feel welcomed, include everyone in a recess game, make someone laugh, listen when others talk, let your classmate go first, be extra kind to the bus driver, thank your teacher for all her/his hard work, etc. Model small acts of kindness and compliment students who are being kind.

Small, spontaneous acts that may take only a brief moment and that doesn't cost anything. Examples: smile, hold a door for someone, give a compliment to a friend, sit by someone who is alone at lunch, make someone new feel welcomed, include everyone in a recess game, make someone laugh, listen when others talk, let your classmate go first, be extra kind to the bus driver, thank your teacher for all her/his hard work, etc. Model small acts of kindness and compliment students who are being kind.- Larger, planned acts that may take more time. Examples: volunteer to be a 'Best Buddy'6 (a buddy for a peer with special needs), help clean up the classroom, donate unwanted clothes or toys to a group in need, write a thank you note to your teacher, invite someone for a play-date that seems to need a friend, clean your bedroom, read a story to a younger student, pass on a book that you enjoyed, bake something to bring into class and share

Other strategies and suggestions:

- Visit The Random Acts of Kindness Foundation website and use the classroom instructional materials for teaching all children and school personnel how to be kind and to inspire cultures of kindness in our homes, schools and communities. Check out the classroom posters, bookmarks, calendars, videoclips, etc. Short, 15 minute Lesson Plans are free and downloadable.

- Promote friendship and respect for differences. Refer to the friendship promotion materials provided in the Comfortable Cafeteria and Refreshing Recess programs (Week 2). Use these to help teach students about how to be a good friend and respect differences. Research has shown that students who perform acts of kindness are more likely to be accepted by peers and have more friends.4 Promote friendships between children with and without disabilities – see Best Buddies.

- Host a 'Kindness Day' routinely (once a week or month). Have students and adults come up with and write down at least 5 different acts of kindness that are not typically done. Have students reflect on the other person's reaction and how doing these acts made them feel.2 The act of remembering kind acts and writing them down actually increases feelings of happiness.1

Website suggestions:

- Random Acts of Kindness Foundation

- Price-Mitchell, M. (2015). The art of kindness: Teaching children to care. ROOTS OF ACTION website.

- Best Buddies - A nonprofit organization promoting opportunities for friendship, integrated employment and leadership development for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (DD).

References: 1 Otake, K., Shimai, S., Tanaka-Matsumi, J., Otsui, K., & Fredrickson, B. (2006). Happy people become happier through kindness: A counting kindnesses intervention. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7, 361-375. 2 Actions for Happiness. (2015). Action 2: Do kind things for others. http://www.actionforhappiness.org/take-action/do-kind-things-for-others 3 Lyubomirsky, S. (2007). The HOW of happiness: A new approach to getting the life you want. London: Penguin Books LTD. 4 Layous, K., Nelson, S. K., Oberle, E., Schonert-Reichl, & Lyubomirsky, S. (2012). Kindness counts: Prompting prosocial behavior in preadolescents boosts peer acceptance and well-being. PLoS ONE 7(12): e51380. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051380 5 The Random Acts of Kindness Foundation (2014). Kindness in the Classroom social and emotional learning curriculum. For grades K-5, 6-8, and high school curriculum guides. Click here for a curriculum overview. Check out their free Kindness Printables: posters, calendars, and bookmarks.

Positive environments (physical, social, emotional, sensory) can help all students participate at their best!

Do what you can to create school environments (classroom, cafeteria, hallways, etc.) that help all students feel good emotionally (calm, safe) and physically (comfortable) and function successfully. So 'tune into' all of the social, physical and sensory aspects of the spaces students spend time in.

Remember that students have varying preferences and needs depending on their unique developmental and neurological makeup. Students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), for example, may be highly sensitive to loud noises or light touch resulting in feeling anxious or 'on edge'. It's important to consider the individual learning needs of ALL students.

Remember that students have varying preferences and needs depending on their unique developmental and neurological makeup. Students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), for example, may be highly sensitive to loud noises or light touch resulting in feeling anxious or 'on edge'. It's important to consider the individual learning needs of ALL students.

Environment-focused intervention simply refers to how changing the environment to meet the needs of a student can foster successful participation.1 The focus is on providing the necessary supports (e.g. physical, social, activity-based), removing barriers, and building strengths.

Simple strategies:

Social – Create inclusive, learning-friendly environments that promote respect for differences (skill-level, cultural, religious, ethnic) and foster family engagement. Make a point to help students without disabilities to respect and include those with special needs. Consider implementing a Best Buddies program. Refer to Embracing Diversity: Toolkit for Creative Inclusive, Learning-Friendly Environments (UNESCO, 2015).2

Social – Create inclusive, learning-friendly environments that promote respect for differences (skill-level, cultural, religious, ethnic) and foster family engagement. Make a point to help students without disabilities to respect and include those with special needs. Consider implementing a Best Buddies program. Refer to Embracing Diversity: Toolkit for Creative Inclusive, Learning-Friendly Environments (UNESCO, 2015).2

Physical – Tune into the physical environment. Are spaces clean and free of clutter? Does it look like a place you would like to spend time in? Make spaces appealing for students! Consider how the classroom or cafeteria layout of tables, desks and chairs influences interaction. Check out, 8 Tips and Tricks to Redesign Your Classroom and Classroom Layout and Design on Pinterest.

Sensory – We are all unique sensory beings and respond to what we feel, see, hear, touch and how we move in our own ways. It is important to teach all students and adults to respect each other's sensory needs (e.g. less noise, more movement, less eye contact). Consult with the school's occupational therapist to learn more about sensory processing. Think about the effects of sensory input, for example:

- Visual input: Lighting – fluorescent lighting does not create the best visual environment for humans! Try turning off a bank of lights in the classroom, bringing an incandescent lamp into the room you work in, or draping thin solid color (blue or green) fabric from the ceiling panels. These fluorescent light filters are available commercially (see Therapy Schoppe®. Think about the effect of color on attention and mood. Blue and green are generally calming; red, orange and yellow are alerting.

Sound: Some students work best with background noise while others prefer quiet. Have noise-reducing headphones or earplugs available and help prepare students ahead of time before entering a noisy environment. Refer to 'Classroom noise management' on Pinterest for ideas on how to regulate sound.

Sound: Some students work best with background noise while others prefer quiet. Have noise-reducing headphones or earplugs available and help prepare students ahead of time before entering a noisy environment. Refer to 'Classroom noise management' on Pinterest for ideas on how to regulate sound.- Movement: Students differ in how much movement they need in order to feel alert and attentive. Overall, it's important to allow changes in body position during quiet work (e.g. standing desks, bean bag corners, chair balls, rocking chairs, or fidget cushions). Remember that even short movement breaks lead to better attending and learning. Even 5 minutes of walking can help regulate mood (e.g. decrease anxiety). Have students who benefit from extra movement run errands for the teacher. Also, visit Fun and Function sensory cushions for seating ideas.

- Touch input: Students vary in the amount of touch they need or want. Some may avoid touch. However, many learn best when they can have their hands on instructional materials. Make sure to offer students a variety of learning materials for hands-on learning. Check out 'Hands on Learning' on Pinterest.

- Smelling Sense: Smells can be calming or alerting. For students who are over-sensitive to smells, try having the child use a scented hand lotion to mask the unpleasant smell (e.g. locker room) and verbally prepare the students for the smell he/she may encounter. See Therapy Street for Kids for more ideas.

- Taste and mouth 'work': Sometimes we regulate how we feel by doing something with our mouths - like sipping water, sucking on a mint, or chewing something crunchy. Although chewing gum is often not allowed in school, it has been shown to increase attention and memory. A recent study showed that 8th grade students who chewed gum performed significantly better than those who didn't in standardized math scores.3 Chewing gum or chewy/crunch foods may also have a calming effect when a student is anxious. Make sure to set limits if gum chewing is allowed – "no noise and no mess". Gum must be discarded in garbage cans. If gum is not allowed, encourage students to keep a water bottle at their desk for sipping.

To view a Power Point presentation on Sensory Processing, click here.

Website resources:

- The Alert Program® for self-regulation. This program helps people regulate their level of alertness to be able to do what they need to do throughout the day using a variety of sensory strategies. Developed by Mary Sue Williams and Sherry Shellenberger, occupational therapists. In their words: “If your body is like a car engine, sometimes it runs on high, sometimes it runs on low, and sometimes it runs just right!” Information about their books and online courses can be found on their website.

- Sensational Brain. Sensory Strategies Classroom Accommodations Checklist. (free resources)

- Article for teachers: Thompson, S. D., & Raisor, J. M. (2013). Meeting the sensory needs of young children. Young Children. National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC). Written by teachers, this article is filled with user-friendly ideas for addressing sensory processing needs in the classroom.

References: 1 Anaby, D. R., Law, M. C., Majnemer, A.,& Feldman, D. (2016). Opening doors to participation of youth with physical disabilities: An intervention study. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 83(2), 83‐90. http://doi:10.1177/0008417415608653 2 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Embracing Diversity: Toolkit for Creative Inclusive, Learning-Friendly Environments. 3 Johnston, C. A., Tyler, C., Stansberry, S. A., Moreno, J., & Foreyt, J. P. (2012). Brief report: gum chewing affects standardized math scores in adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 455-459.

10 Approaches for Promoting School Mental Health

The following are evidence-based approaches applied in schools for the purpose of mental health promotion, prevention, and intervention. Schools often apply several approaches such as Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) and Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports (PBIS). Mental health literacy is an essential part of mental health promotion. A description of each is provided along with implementation examples and key references.

A 2-page summary handout of this content can be downloaded and printed for easy reference here.

"I will try to create more happiness and less unhappiness in the world around me." (Action for Happiness pledge)

Mental health literacy, refers to providing all children and youth with a working knowledge of mental health - what it is and how to take care of it.1 It involves having knowledge and skills about:

- positive mental health and how to take care of one's mental health;

- early signs of mental ill-health and symptoms associated with mental disorders;

- how to seek help when feeling unwell emotionally;

- effective self-help strategies for mild problems; and

- how to support others facing a mental health crisis2

Simple strategies for promoting mental health literacy: Embed information about mental health throughout the school day during language arts, art, health, therapy sessions, and even during lunch and recess! Be creative! Collaborate with your health educator, school nurse, occupational therapist, and school counselor.

Simple strategies for promoting mental health literacy: Embed information about mental health throughout the school day during language arts, art, health, therapy sessions, and even during lunch and recess! Be creative! Collaborate with your health educator, school nurse, occupational therapist, and school counselor.

Primary grades: Use the following coloring and handwriting sheets focusing on positive mental health, character strengths, coping strategies, etc.

Growing Powerful coloring sheet. Have children color this sheet. Use this coloring sheet as a tool to talk with students about what they can do to take care of their mental health (i.e. feel good emotionally and do well functionally) such as: doing healthy and enjoyable activities, getting enough rest and exercise, talking about their feelings, etc.

Powering Up to Happiness Striker reading and handwriting sheet. Use this sheet to talk about what 'happiness' is – that when we feel happy, we are mentally healthy. Help them realize that they can control their feelings of happiness by what they do (doing activities they find enjoyable, getting enough rest) and how they think (thinking positive, stopping negative thoughts).

Happiness Striker coloring sheet. Review things that students can do on the Happiness Striker to be mentally healthy. During the day, have them take out this sheet and color in the section representing what they’ve done.

Power to Control Anger and Fear handwriting sheets. Teach students that coping with challenging emotions like fear and anger is a normal part of life. All people go through challenges, big and small, and need to learn how to deal with them. Use these handwriting sheets to help students learn about the feelings of anger and fear and things they can do to help them cope.

Elementary and middle school: Consider using books, apps, and handouts to learn and talk about mental health.

Apps for Mental Health Promotion: This handout provides a list of apps that can be used on iPads and iPhones to learn about topics related to mental health.

Books to read: This is a list of books to read about mental health promotion. Make sure to have these available in your classroom or school's library.

Success Story! Talk about it Tuesdays! Jenna Tousignant, RN (school nurse) and Marta Kilrain, OT (occupational therapist) teamed up to provide a weekly mental health literacy story time for 3rd graders at Strafford Learning Center in New Hampshire. Jenny would read a book on a subject related to mental health and Marta would follow up with a short activity. One week, the book Worry Says What? was read to help students learn about worry and how to silence worrying. Marta had the students make motivational pencil toppers!

Success Story! Talk about it Tuesdays! Jenna Tousignant, RN (school nurse) and Marta Kilrain, OT (occupational therapist) teamed up to provide a weekly mental health literacy story time for 3rd graders at Strafford Learning Center in New Hampshire. Jenny would read a book on a subject related to mental health and Marta would follow up with a short activity. One week, the book Worry Says What? was read to help students learn about worry and how to silence worrying. Marta had the students make motivational pencil toppers!

Handouts for students and school personnel: Use these to have discussions about positive mental health.

Handouts for students and school personnel: Use these to have discussions about positive mental health.

What is Mental Health information sheet. Have students read and discuss the contents of this information sheet to begin teaching them about mental health as a positive state of functioning. Have them tune into their own mental health.

How to Take Care of Your Mental Health information sheet. Have students read and discuss the contents of this information sheet. Encourage them to identify ways in which they can take care of and improve their mental health.

School Staff Tips for Promoting Mental Health information sheet. Pass these out in the teacher lounge or in team meetings to raise awareness about positive mental health and what school staff can do to promote mental well-being.

Host Children's Mental Health Awareness Day activities:

National Children's Mental Health Awareness Day is celebrated each year during May and is sponsored by SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration). The purpose of this day is to raise everyone's awareness about the importance of positive mental health for overall health and daily functioning. As a team, do something to raise awareness of children's mental health.

Don't wait until May! Begin planning for this event in the beginning of the school year!

Here's what one school did! Under the leadership of Brenda Allen, MS, OTR/L at Muskingum County Starlight School (Zanesville, Ohio), the school team began to learn about positive mental health and plan for a May Children's Mental Health Fair in the Fall. Ten elementary classrooms worked with high school representatives from a communications class to plan a display for the event. Each class committed to learning about and preparing materials and activities for one of the 10 Actions for Happiness (www.actionforhappiness.org). Here's what Brenda said about the event:

Here's what one school did! Under the leadership of Brenda Allen, MS, OTR/L at Muskingum County Starlight School (Zanesville, Ohio), the school team began to learn about positive mental health and plan for a May Children's Mental Health Fair in the Fall. Ten elementary classrooms worked with high school representatives from a communications class to plan a display for the event. Each class committed to learning about and preparing materials and activities for one of the 10 Actions for Happiness (www.actionforhappiness.org). Here's what Brenda said about the event:

Preschoolers were involved in morning group mental health activities. School age students had an afternoon assembly and invited parents. Each school age class stood up and explained their display. At the end everyone got a certificate of appreciation for Mental Health Awareness. At the beginning and end of the assembly we said the pledge, "I will try to create more happiness and less unhappiness in the world around me."

Bookmarks: Print out and share the 'Be Kind to Your Mind' bookmarks!

Bookmarks: Print out and share the 'Be Kind to Your Mind' bookmarks!

Posters: Make mental health awareness posters for your school bulletin boards, hallways, and classrooms. These are free!

Every Moment Counts "Be Kind to Your Mind" posters (see downloadables on side bar)

Action for Happiness posters for children

Mental health literacy courses and educational materials for school and community providers:

Youth Mental Health First Aid (YMHFA) training courses educate adults on how to provide support for adolescents showing symptoms of a mental health challenges until professional help is obtained.3 Randomized control trials comparing Mental Health First Aid course attendees with wait-list controls found improvements in knowledge, helping behaviors, and stigmatizing attitudes.2 This is an 8-hour course developed for any adults who work with youth in schools or the community. To register for a course, go to www.mentalhealthfirstaid.org

Youth Mental Health First Aid (YMHFA) training courses educate adults on how to provide support for adolescents showing symptoms of a mental health challenges until professional help is obtained.3 Randomized control trials comparing Mental Health First Aid course attendees with wait-list controls found improvements in knowledge, helping behaviors, and stigmatizing attitudes.2 This is an 8-hour course developed for any adults who work with youth in schools or the community. To register for a course, go to www.mentalhealthfirstaid.org- Minnesota Association for Children’s Mental – Mental Health Fact Sheets.

These 2-page fact sheets provide useful information about common mental disorders (e.g. anxiety, depression, ADHD) and practical classroom strategies for helping students succeed in school. To download these fact sheets, refer to the Publications tab and sign up to receive free copies. An Educators Guide to Children's Mental Health and Children's Mental Health Classroom Activities are publications available for purchase under Publications.

These 2-page fact sheets provide useful information about common mental disorders (e.g. anxiety, depression, ADHD) and practical classroom strategies for helping students succeed in school. To download these fact sheets, refer to the Publications tab and sign up to receive free copies. An Educators Guide to Children's Mental Health and Children's Mental Health Classroom Activities are publications available for purchase under Publications. - Teenmentalhealth.org – This website is committed to

providing high quality mental health literacy information, research, education, and resources for educators, teens, and parents. Learn about the Mental Health & High School Curriculum Guide (version 3, 2017) by Kutcher & Wei which is being used in Canada and Washington state. This guide provides information for teachers on how to implement a comprehensive, system-wide approach to teaching mental health literacy as a part of the health curriculum. As of 2020, the guide is free and downloadable on the teenmentalhealth.org website. Information included: positive mental health, symptoms of mental disorders, reducing symptoms, and promoting help-seeking behavior. Research has demonstrated that the 6 week program was effective in improving mental health knowledge and attitudes toward mental illness.4

providing high quality mental health literacy information, research, education, and resources for educators, teens, and parents. Learn about the Mental Health & High School Curriculum Guide (version 3, 2017) by Kutcher & Wei which is being used in Canada and Washington state. This guide provides information for teachers on how to implement a comprehensive, system-wide approach to teaching mental health literacy as a part of the health curriculum. As of 2020, the guide is free and downloadable on the teenmentalhealth.org website. Information included: positive mental health, symptoms of mental disorders, reducing symptoms, and promoting help-seeking behavior. Research has demonstrated that the 6 week program was effective in improving mental health knowledge and attitudes toward mental illness.4 - American Occupational Therapy Association’s (AOTA) –

School Mental Health toolkit. This is a compilation of information sheets on issues related to mental health such as common disorders (e.g. anxiety), factors that place children at-risk (grieving & loss, obesity, bullying), and environmental stressors (e.g. trauma, cafeteria issues). Each information sheet provides how the issue impacts participation and strategies for mental health promotion, prevention, and intervention.

School Mental Health toolkit. This is a compilation of information sheets on issues related to mental health such as common disorders (e.g. anxiety), factors that place children at-risk (grieving & loss, obesity, bullying), and environmental stressors (e.g. trauma, cafeteria issues). Each information sheet provides how the issue impacts participation and strategies for mental health promotion, prevention, and intervention.

References:

1 Barry, M. M., & Jenkins, R. (2007). Implementing mental health promotion. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier.

2 Jorm, A. (2012). Mental health literacy: Empowering the community to take action for better mental health. American Psychologist, 67, 231-243.

3 Kelly, C. M., Mithen, J. M., Fischer, J., A., Kitchener, B. A., Jorm, A. J., Lowe, A., & Scanlan, C. (2011). Youth mental health first aid: a description of the program and an initial evaluation. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 5(4), 1-9.

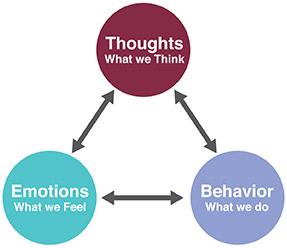

4 Milin, R. et al. (2016). Impact of a mental health curriculum on knowledge and stigma among high school students: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(5), 383-391.Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) is a framework used to guide the process of helping children and youth develop critical skills for life – how to get along with others, handle challenges, and behave ethically. Programs that foster SEL help children recognize feelings and think about how feelings influence behavior.

Specifically, programs that foster SEL help children to recognize and manage emotions, think about their feelings and how one should act, regulate behavior based on thoughtful decision making, and acquire important social skills for developing healthy relationships in life.1 In a 2011 meta-analysis of 270 studies, students participating in SEL programs demonstrate increased academic performance, social and emotional functioning, and reduced behavior problems.2 Further, SEL programming can have a positive impact up to 18 years later on academics and emotional well-being.3

Specifically, programs that foster SEL help children to recognize and manage emotions, think about their feelings and how one should act, regulate behavior based on thoughtful decision making, and acquire important social skills for developing healthy relationships in life.1 In a 2011 meta-analysis of 270 studies, students participating in SEL programs demonstrate increased academic performance, social and emotional functioning, and reduced behavior problems.2 Further, SEL programming can have a positive impact up to 18 years later on academics and emotional well-being.3

Check out the SEL Interactive Framework to learn about the 5 core SEL competencies including: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making. For more information, refer to the Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL). Currently, all 50 states have preschool SEL standards and many states have SEL integrated in their academic standards.4,5

Check out the SEL Interactive Framework to learn about the 5 core SEL competencies including: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making. For more information, refer to the Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL). Currently, all 50 states have preschool SEL standards and many states have SEL integrated in their academic standards.4,5

Things you can do starting NOW:

- Select BOOKS that promote SEL by helping students learn about and process feelings and life events (sometimes referred to as bibliotherapy). Select books that focus on characters who experience different feelings and talk about it afterwards. Pose questions to foster reflection on how to verbalize and manage emotions such as, "What do you think he was feelings?"; "What do you think she should do?". Suggested reading lists: Younger children; for middle school students, see Carnegie Library's bibliotherapy list.

- Teach a feeling vocabulary using a variety of embedded strategies throughout the day using games, craft activities, songs and storybooks that focus on feelings. Encourage students to tune-into other's feelings and respond with empathy. Express your own feelings out loud (e.g. 'that was frustrating for me') and demonstrate positive ways for dealing with feelings (e.g. 'I better take a deep breath').

- Embed feeling activities into language arts, art and handwriting instruction. Use coloring and handwriting sheets developed for Every Moment Counts – see Mental Health Literacy and Mental Health Awareness Day Materials (sidebar downloads)

- Use color to help students learn about emotions. Teach feeling words and a range of intensity using a color wheel. See do2learn's emotion color wheel.

- Observe children's facial expression, body language, and tone of voice in order to help label their feelings based on your observations (e.g. "You seem a bit discouraged", "You look excited about going to recess").

- Teach students about their feelings and how to regulate their emotional state using The Zones of Regulation (Kuypers, 2011). Lessons and learning activities are designed to help students recognize their Zone (moods/alertness) and use strategies (sensory supports, calming techniques) to regulate their Zone in order to help them learn and interact effectively with others. This curriculum can be used by an interdisciplinary team.

Other suggestions:

Find out if your school has adopted an SEL curriculum (e.g. Paths® Program - Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies.

Find out if your school has adopted an SEL curriculum (e.g. Paths® Program - Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies.

Learn about SEL at www.casel.org (information, research, webinars, educational materials)

Read the CASEL Guide to Schoolwide Social and Emotional Learning

See if your state has adopted SEL academic standards at the CASEL State Scan. As an example, read Ohio's SEL Standards to learn SEL goals per grade level.

References: 1 Elias, M. J., et al. (1997). Promoting social and emotional learning: Guidelines for educators. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum. 2 Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students' social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82 (1), 405–432. doi:10.1111/j.1467- 8624.2010.01564.x 3 Taylor, R. D., Oberle, E., Durlak, J. A, & Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Promoting Positive Youth Development Through School‐Based Social and Emotional Learning Interventions: A Meta‐Analysis of Follow‐Up Effects. Child Development, 88(4), Pages 1156–1171. 4 Durlak, J. A., Domitrovich, C. E., Weissberg, R. P., & Gullotta, T. P. (Eds.) (2015). Handbook of Social and Emotional Learning: Research and Practice. Guilford Press. 5 Zinsser, K. M., Weissberg, R. P., & Dusenbury, L. (2013). Aligning preschool through high school social and emotional learning standards: A critical and doable next step.

We are all unique sensory beings and respond to what we feel, see, hear, touch and how we move in our own ways. How we process sensory information (sensory processing) often influences how we self-regulate our emotions and behavior.

Sensory processing is a person's way of noticing and responding to sensory messages from their bodies and the environment.1 Persons with disabilities and/or mental health difficulties may experience everyday sensations with more or less intensity than those without such challenges. Such sensory differences may influence a person’s behavior, social interaction and regulation of emotions. It is important to teach all students and adults to respect each other's sensory needs (e.g. less noise, more movement, less eye contact). Consult with the school's occupational therapist to learn more about sensory processing. Also, refer to the SPD Foundation for further information on sensory processing disorder (SPD) at the SPD Foundation and the STAR Institute. To learn more about sensory processing, click here to review a powerpoint presentation entitled "Creating Sensory Friendly Environments to Promote Positive Participation for Students With and Without Disabilities" (Bazyk, 2015). Better yet, have your school's occupational therapist present this as an inservice. The PPT gives a brief summary of sensory processing, the ALERT Program, and Zones of Regulation framework.

Sensory processing is a person's way of noticing and responding to sensory messages from their bodies and the environment.1 Persons with disabilities and/or mental health difficulties may experience everyday sensations with more or less intensity than those without such challenges. Such sensory differences may influence a person’s behavior, social interaction and regulation of emotions. It is important to teach all students and adults to respect each other's sensory needs (e.g. less noise, more movement, less eye contact). Consult with the school's occupational therapist to learn more about sensory processing. Also, refer to the SPD Foundation for further information on sensory processing disorder (SPD) at the SPD Foundation and the STAR Institute. To learn more about sensory processing, click here to review a powerpoint presentation entitled "Creating Sensory Friendly Environments to Promote Positive Participation for Students With and Without Disabilities" (Bazyk, 2015). Better yet, have your school's occupational therapist present this as an inservice. The PPT gives a brief summary of sensory processing, the ALERT Program, and Zones of Regulation framework.

Self-regulation is the ability to manage and control our emotions and behavior. Self-regulation helps us do what we need to do throughout the day. Consider teaching students how to self-regulate using The Zones of Regulation: A Framework for Self-Regulation & Emotional Control (Kuypers, 2011).2 Contact your school's occupational therapist and school counselor to see if they might co-teach this information to your students. Think of ways you might embed this into the curriculum. Refer to the Zones of Regulation to purchase the book, posters, and app.

The Alert Program® for self-regulation is also useful. This program helps people regulate their level of alertness to be able to do what they need to do throughout the day using a variety of sensory strategies.3 Developed by Mary Sue Williams and Sherry Shellenberger, occupational therapists. In their words: “If your body is like a car engine, sometimes it runs on high, sometimes it runs on low, and sometimes it runs just right!” Information about their books and online courses can be found on their website, www.alertprogram.com.